Woking Male Invalid Convict Prison for male convicts was opened in 1859. This prison, created to manage the ever-increasing demand for a place to house invalided convicts, took in those considered too weak to follow the expected heavy labour associated with general prisons. Those with epilepsy, blindness, mental incapacitation, physical disability and ailments associated with old age, were all held in this new prison. It was felt at the time that the healthy atmosphere and the slightly less rigorous regime, would prevent the decline and death so common for this subset seen in standard gaols.

January 1970 – Woking Review.

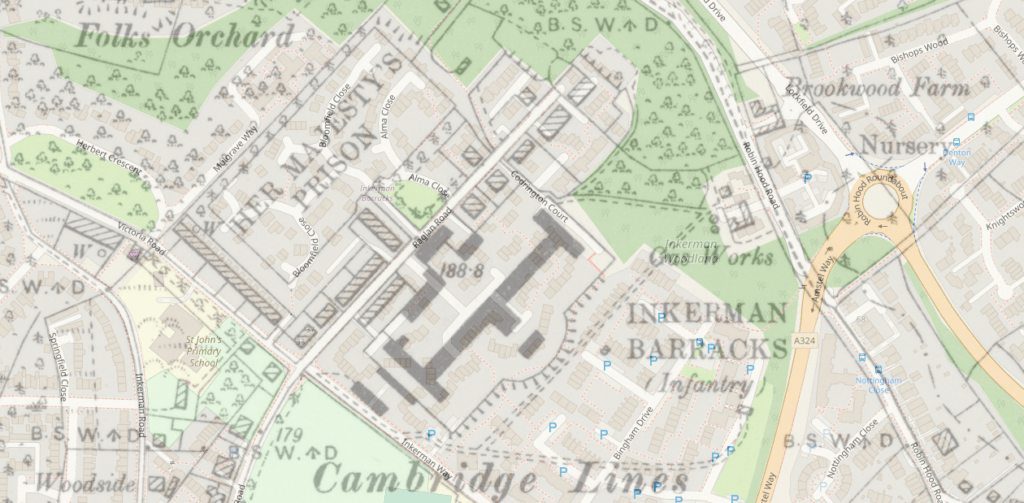

Construction began on Woking Prison shortly after the purchase of some 64 acres from the London Necropolis company in 1858; the foundation stone of the chapel was laid by the Honourable Spencer Walpole, the then Secretary of State. The first tranche of prisoners walked through the gates in April 1859 to be supervised by the first Governor of Woking, John Sandham Warren. Their role was to aid in the construction of Woking Prison alongside paid builders and were chosen because of their good behavior, labouring skills and they were nearing the end of their sentence.

By March 1860, Woking Prison had taken over from the temporary Invalid Prison at Lewes as it was deemed to have better facilities for dealing with the disabled and mentally infirm.

The warders and prison overseers were housed in specially fabricated dwellings on the edge of the grounds, close enough to manage the site but far enough away to protect their families from dangerous and, sometimes, disturbed inmates.

The 1861 census lists the Governor as John Sandham Warren, the deputy Governor Samuel Finnie, a Chaplain, a Chief medical officer, an Assistant Medical Officer and myriad of other warders, schoolmasters, scripture readers, stewards, clerks, porters, and tailors. There was even master shoe makers to instruct inmates in how to carry out their designated work, as well as to teach them skills to be used on their release.

The prison was an absolute hive of industry, as it needed to be, as the cost for retaining inmates in the level of comfort provided at the invalid prison, was over double that of prisons elsewhere. Woking Prison as a result, was often referred to as ‘Woking Palace’.

In 1869 the site was expanded to include a women’s prison, the first inmates arrived from Parkhurst Prison on the Isle of Wight that same year.

In 1875, Woking Prison formally opened its doors formally to the mentally incapacitated. Whilst it was never declared a criminal asylum under the Act of 1860, it housed those who became insane during their sentence. They were put under the care of the medical officers until a few weeks before release, at which point they would be transferred to Broadmoor for certification into a civil asylum or another form of care.

In time, Woking Prison had a wing for the criminally insane and supported those patients in their transition to an asylum at the end of their sentence.

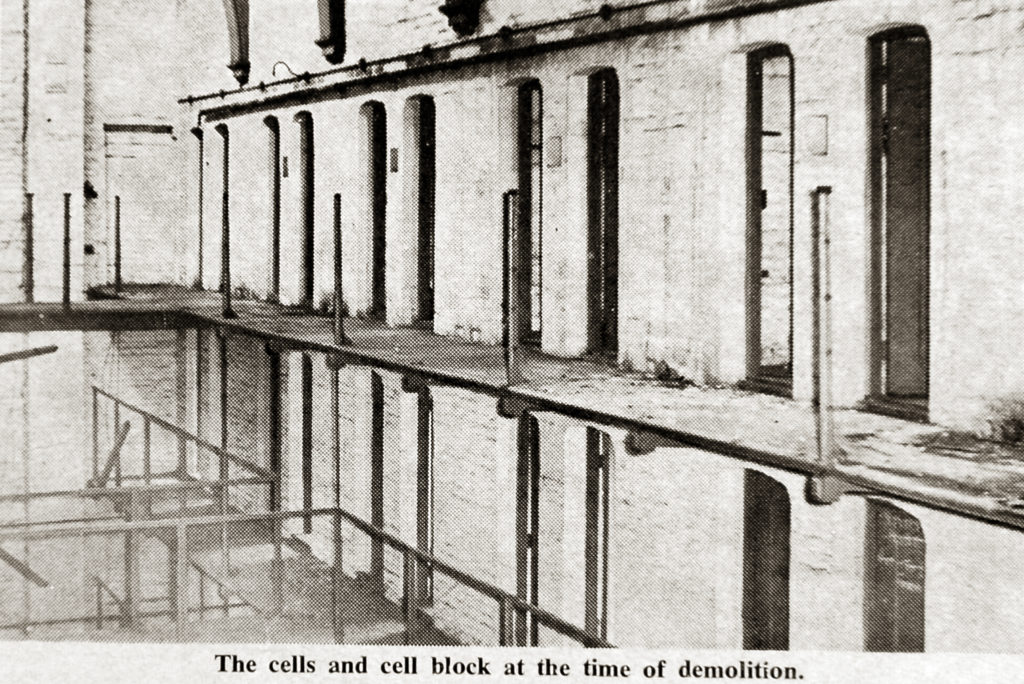

- Wing consisted of 3 floors, stanchion railing raised (to avoid inmates jumping), brick building for lower floors and corrugated iron at top so men couldn’t hang themselves.

- Window loops and bars protected to avoid hanging danger, hot and cold baths for cleanliness and wellbeing and iron besteads recommended to be replaced with wooden (to stop inmates impaling each other or themselves)

- Whilst ‘normal’ prisoners looked forward to Woking, the insane despised it as ‘…great disadvantages in not being able to allow them asylum indulgences, such as many had formerly had enjoyed, especially the much coveted tobacco… [and] beer’

- Despite this, Lunatics could do light farm work, work in the washroom, cleaning wood floors, mending clothes and asphalting the walkways of the prison in return for bread and cocoa, paper, pencils and paints

- Opportunities for ‘recreation’ – ‘Many were musically inclined, and a few managed to make violins; and some contrived banjos out of American cheese boxes…Others again managed to make flutes and pipes’

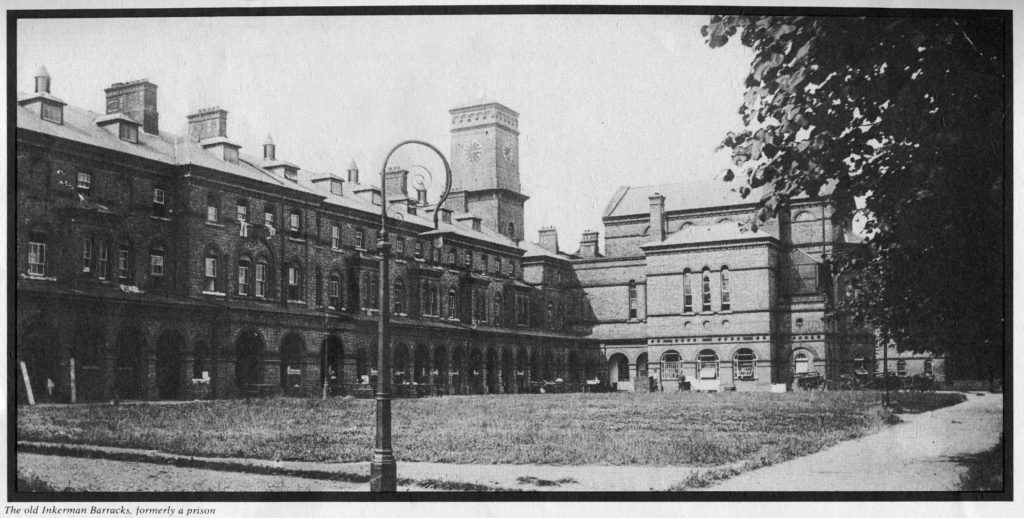

The male prison was closed finally in 1889 due to a decline in the number of chronically ill in the criminal class: the female wing following suit in 1895 and the site’s ownership transferred to the military.

Notorious Inmates at Woking Male Invalid Convict Prison

John Lynch – The Bold Fenian Man

Alexander Moir – The Merciless Murderer

William Strahan – The Bent Banker

Aaron Rungay – The Water Boatman

William Privett – The Melancholy Pickpocket

Joseph Richards – The Beast of Brecon

Emery Spriggs – The Dark Shooter

Enoch Hall – The Ab-duck-tor

Edward Smith – The Grieving Thief

Woking Prisoner Entry Registrations

1871-1880

1881-1889

Woking Prison Staff

Captain John Sandham Warren – First Governor of Woking Male Invalid Convict Prison