Medical Galvanism: The therapeutic application of electricity to the body.

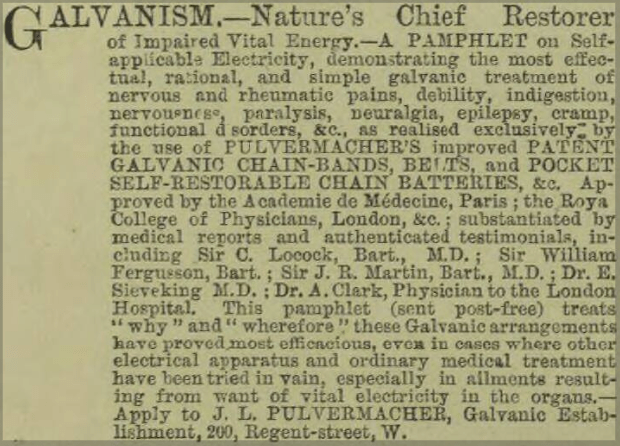

Galvanism is not something you would necessarily assume to be tied to health. But one of the definitions “The therapeutic use of currents” makes it clear that this has often been the case. Today we use currents in pacemakers and defibrillators, but in the Victorian era the uses were wide ranging and often disturbing.

The application of electrical probes, and the passing through of a current to cause muscle contraction, could be considered a sensible course of action in those who suffered from paralysis of body or face. Indeed it’s still in use today, in the form of Electro-Convulsive Therapy practised on patients who experience acute depressive episodes. But for the inmates of institutions, the shock treatments were applied for various reasons, both as a curative and to test the veracity of their illnesses.

From the healing of fissures, acne, piles, mania, melancholy, pain… for a battery of ailments there was a “battery” to cure. For those conditions, a little more difficult to put a name to, such as unspecified wasting of muscles or the incidental paralysis, this is where electrification became even more commonplace, if inhumane to modern eyes.

John Campbell was the chief medical officer at Woking Convict Invalid Prison. His role was to ensure the safety of the convicts, some 700 at any one time, under his care. Pat of his role was to certify them as ‘of sound body’ for labour or, when the need arose, to deem them well enough to endure corporal punishment. Every convict suspected to be too infirm to carry out hard labour, was transferred from all the large prisons across England to his domain. Whilst the Governor would make decisions regarding punishments or praise, these decisions would have had to have been ratified by the medical officer: such was his power. Woe betide the malingerer attempting to avoid his government enforced term of servitude.

One such malingerer had been bed bound for nearly 3 years, having convinced the medical officers at his previous prison that he was completely incapable of sitting, standing, or managing any form of work. Campbell was less than impressed and, having noted the prisoners legs had none of the expected muscle wastage, he became suspicious.

The prisoner claimed his lower limbs hurt so much, that he couldn’t bear the touch of so much as even a blanket and thus a cradle had been erected which held the blankets off his legs whilst he slept. Campbell ordered this removed and during the course of his night in the hospital ward, it was clear the prisoner’s legs moved as normal whilst sleeping.

Still the prisoner denied the ability to walk, and flatly refused to entertain the possibility of an attempt, so finally Campbell resorted to galvanism. As he himself stated “patients suffering from real disease gladly submit to this or any other remedy; but malingerers show a great repugnance to it”. He strapped the man to the table and applied the chemical battery to his legs, the effect, whilst not instantaneous was definitely near miraculous. Within 10 days, when Campbell returned to administer another daily dose, he was informed that the patient had “walked down to the exercise yard with the other inmates”.

Whilst by no means the only incident of the sort in Woking Prison, this reminiscence of the Doctor left none in any doubt that galvanism would remain a final test for the invalided convict. Even today, there are experimental techniques using this same premise and, whilst they are carried out with compassion (and anaesthesia), it’s clear that the many uses of the electrical cure will be with us for some time.