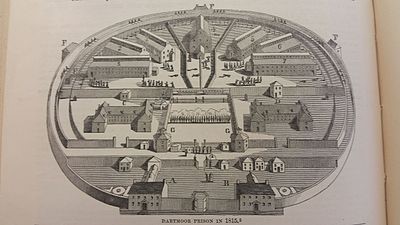

Nestled in the bosom of a misty set of hills, Dartmoor Prison with its circular sides has been in use since the Napoleonic wars. French, American and English prisoners have walked through its gates and not all have left through that self-same portal, at least not upright.

The prison continues to function and thus the museum itself, now occupying the old dairy buildings, is far less impressive from the outside than what we were expecting, indeed it seemed from the outset to be a shed: but looks can deceive. The ordinary façade hid an extraordinary interior and the history held therein far exceeded our expectations.

On chips of stones we crunched our way to the entrance, greeted by a dozen or more gaudily painted gnomes and buddhas. I checked, we hadn’t accidently imbibed any LSD on our journey over the moors, and they were completely real. As it transpires, one of the many wares the prison exports are painted horticultural sculptures. Indeed, this view that industry was conducive to good behaviour and a sense of purpose for prisoners, was a belief that stretched back to the Victorian era.

In the first area we were treated to a potted history of the prison’s origins. Constructed between 1806-9, it was built to house prisoners of the Napoleonic wars when it was deemed unsafe to hold them on prison hulks. They were later joined by American prisoners from the 1812 war and by 1816, 6.5k American prisoners were held here. The prisoners largely ran their own affairs, from theatre to markets, they self-governed. The American troops were conveyed home once a peace treaty had been ratified by the US senate, and by 1851 Dartmoor became a civilian prison.

The greatest calamity in the prison’s history occurred on the 24th January 1932. Over the course of 2 hours, inmates attacked staff, released convicts from solitary confinement, and caused untold damage to the property itself. The greatest victim of the riot, however, were the prisoner logbooks. Priceless, irreplaceable, they were burned during the uprising: denying us and future historians a full understanding of the prison’s working in the 19th century.

From these history displays, we travelled to the contraband rooms: give an inmate enough time and he’ll make a helicopter out of toothbrushes! It was utterly fascinating to see what the prisoners created, both from the weaponization of toothpicks to the ingenuity of hiding mobile phones in radios. Whilst inmates’ attentions are diverted elsewhere these days, see below, it’s still remarkable to witness the sheer inventiveness.

In the last areas of the museum, we were shown some of the autobiographies of some of its most famous, or should that be infamous, inmates. From Australia’s most well-known bushranger to early Irish republicans, English authors and associates of the Kray’s, Dartmoor has seen it all.

Interspersed between gaudily dressed mannequins and printed bits of paper, prison artefacts tangible story of order maintained in trying times. Trying for both inmates, with only the same Victorian rocks for comfort, and for the staff sent there to ensure rehabilitation. We were presented constantly with the contrast between then and now: Dartmoor as it was and as it is… and as it will be no more. As of the 25th October 2019, HMP Dartmoor has scheduled to close in 2023: so, get down there while you still can.

Spookiness

👻/5

Education

📖 📖 📖 📖 /5

Value for money

💰 💰 💰 /5

Overall

🎯🎯🎯/5

Not quite a riot but well worth a visit