Early Life

Joseph Richards, otherwise known as Joseph Penkefyl, was a man of indiscriminate libation and inveterate dissipation. He was born around the year 1795 and lived in a rural welsh mining community in Brecon, for most of his life. Employed as a watchman in Sirhowy Iron Company[1], he lived with his wife, their young son, her two children from a previous marriage and, to add overcrowding to the situation, her two brothers. Morris and John Davies had been living with the couple since the former brother had returned from America: five months in and tempers were beginning to fray.

Joseph worked nights and, as any modern medic will tell you, the impact of night working on the psyche is significant. Disturbed sleep and the loneliness of being on an entirely different circadian rhythm to those around you, builds stress at an alarming rate[2].

The house the Richards’ lived in was miniscule: two rooms upstairs, two down. Joseph had given up the master bedroom to his houseguests and shared a room with his thirteen-year-old step-son, just behind the kitchen and below creaking floors with no insulation or separation. The other boys aged ten and six, slept in the same room as their mother.

Joseph found the lack of sleep unbearable and the enforced insomnia proved to be the tinderbox which would destroy a family forever.

The Crime

On the 6th June 1855, Joseph returned later than expected. Normally home a little after 9 am; he sauntered in exhausted and possibly a little worse for drink over an hour later. The house was full to bursting with the eldest boy and the younger brother-in-law both struck down with an ague (feverous shakes). His wife was nowhere to be seen, but the eldest brother-in-Law, John Morris, was already on his way to pushing the Breconshire beast beyond breaking point.

The house had little insulation and sound travelled far. The brothers bedroom was directly above that of the master of the house and his young stepson. Any movement was instantly broadcast through the thin flooring planks and the soused Richards, hearing something not to his liking, became irate.

On John Davies descent down the stairs, there was a slight commotion. Joseph made his discontentment known, with a grumbling retort heard by both the invalids in their separate rooms, before stomping out of the house: no more was heard until a little after 2pm, when Morris wended his shaking way down the stairs.

What happened next was disputed at the court case. According to Morris, Joseph Richards had stormed back into the tiny kitchen, accused John Davies of “living on another man’s back”: in other words, taking advantage of his hospitality. John denied this vehemently and joseph left the room for mere minutes, in high dudgeon. He returned soon after having snatched the bread knife from the kitchen table and stabbed John Davies in the stomach, just below the breastbone.

He turned on the ailing Morris and impaled him too, but thankfully the knife struck the bone of his hip. All three of the men tumbled into the street. John declaring that he had been killed, fell to his knees and bared his vitals and viscera to a local neighbour Jennett Morgan. Mrs Morgan on seeing the condition of the brothers, cried out to Joseph “Oh you villain, you have killed him!”. Jennett and Morris helped John back into the house, but he had already begun to fade: within half an hour, he had bled out.

In the meantime, Joseph, quite calmly and still drunk, walked the half mile to the local police station and turned himself and the bloodied implement of murder in to the officer, Edward Bennett.

On Tuesday 31st of July 1855, Joseph Richards faced the dock. Dressed in his casual clothes, and with no counsel or legal representation, he stood before judge and jury charged with the crime of wilful murder. According to contemporary sources he treated the entire matter as a great joke, no doubt feeling that his life would be spared. But as the case dragged on, this expectation seemed misplaced.

The prisoner stated that both brothers had attacked him and that the stabbings, one fatal and one debilitating, were in consequence of that attack whilst he had been holding a knife, a knife held innocently at that time to cut some tobacco.

The witnesses disputed this vehemently. Jennett Morgan even went so far as to explain that Joseph’s ire came, not only from the disturbance of sleep, but that one brother coming into money had given none to his Joseph or his wife for bed and board! There was a clear and evident motive and none spoke in his defence.

The police officer attested to his alcohol consumption, the stepson, to previous altercations, and the surviving brother, to the foul deed itself. The Jury were unanimous in their decision: Wilful Murder.

The judge donned his ominous black cap and, in bleakest blackest tones, he expatiated the sentence.

“Joseph Richards, you have been convicted by a jury of your countrymen of wilfull murder, and I must say that I entirely concur in the verdict which the jury have brought in. It seems to me that you had a wicked disposition, actuated by malice against the deceased, and that you stabbed him to death without provocation. The story that you told before the Magistrates was highly improbable, and is contradicted by witnesses examined here to day, there-fore, without provocation you have imbrued your hands in the blood of your fellow mortal. For this you must prepare to die; and I earnestly implore you to prepare for the awful change – There is no hope for you now in this world; repent of your crime and ask of Heaven for forgiveness. You must make preparation, and I do earnestly advise you to listen to the consolations of religion so that you may be in a fit state to ask pardon of your Maker, and to appear in his presence.

I have now to pronounce upon you the awful sentence of Death, that for this offence you will be taken to the place from whence you came, and thence to the place of execution, and there be hanged by the neck until you are dead, and that your body shall be buried in the precincts of the gaol in which you shall be last confined, and may the Lord have mercy upon your soul.”[3]

At this, the grim reality of his future, or lack thereof, the levity he had maintained during the trial was punctured. Joseph yelled out and was remanded in custody.

Within a fortnight of this dire pronouncement, a reprieve was granted for reasons undisclosed, and instead of the gallows, Joseph was sentenced to transportation for life[4].

Imprisonment

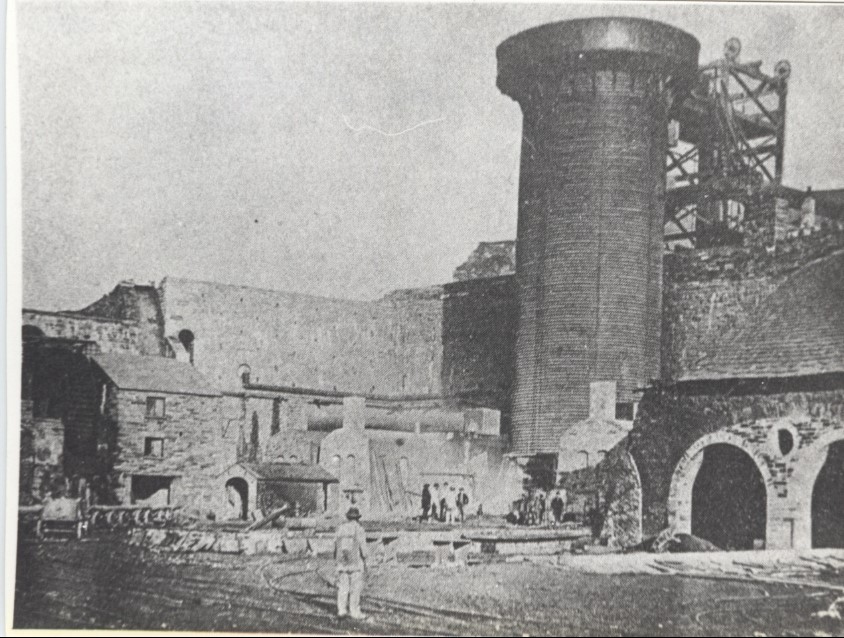

For two months after this clemency, Joseph was held at Brecon County Gaol in seclusion and from there transferred on to Millbank to fulfil the obligatory stint in the Separate system. Within two months, an old chest complaint reared its ugly head and Joseph, aged 60, could not be expected to be transported. He was transferred again, on new year’s eve, this time to a hulk designed for invalids, the “Stirling Castle”[5]. It was a despicable wreck of a ship, filled to the brim with the invalided, maimed and infectious. Hygiene was dire, consumption was rife, and the asthma which carried him to the Castle, miraculously failed to carry him off entirely. He was moved again on the 6th July 1856, to the healthy wholesome air of Dartmoor Prison[6]: a favourite for those of a less than sturdy constitution in the 1850s.

Despite fresh air, and a slightly lighter workload, Richards failed to thrive and was returned to the invalids who, after the Stirling Castle burnt down, were housed in temporary accommodation at Lewes Prison. This group were awaiting the completion of the country’s first invalid establishment, Woking Convict Invalid Prison.

On the 22nd March 1860 Richards, alongside other criminal invalids, was transferred to Woking where he would spent the rest of his sentence. He applied to be licenced at least four times, each time rejected until finally, on 18th August 1869, 14 years after his incarceration, Joseph was released.

Aftermath

It is entirely unknown what Joseph did after his release. Did

he return to his tiny mining village to find his wife? Did he want to re-join

his family? What is known is that she had been referring to herself as his

widow[7]

since at least 1861, so likely did not intend to reunite with the man who had

murdered her brother.

[1] Britishnewspaperarchive.co.uk. (2020). Reading Mercury 4 August 1855. [online] Available at:

[Accessed 25 Feb. 2020].Register | British Newspaper Archive

Register to get involved in the biggest newspaper digitisation project that’s ever taken place in the UK!

[2] Ferri, P., Guadi, M., Marcheselli, L. and Balduzzi, S. (2016). The impact of shift work on the psychological and physical health. [online] NCBI. Available at: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5028173/ [Accessed 25 Feb. 2020].

[3] Britishnewspaperarchive.co.uk. (2020). Hereford Times – Saturday 4 August 1855. [online] Available at:

[Accessed 25 Feb. 2020].Register | British Newspaper Archive

Register to get involved in the biggest newspaper digitisation project that’s ever taken place in the UK!

[4] Britishnewspaperarchive.co.uk. (2020). Brighton Gazette 16 August 1855. [online] Available at:

[Accessed 25 Feb. 2020].Register | British Newspaper Archive

Register to get involved in the biggest newspaper digitisation project that’s ever taken place in the UK!

[5] Search.findmypast.co.uk. (2020). Prison Licence – Joseph Richards. [online] Available at:

[Accessed 25 Feb. 2020].Create an account today

Create an account for free with Findmypast to discover your family history and build a family tree. Search birth records, census data, death records and more.

[6] Ibid – 5

[7] findmypast.co.uk. (2020). 1861 Census. [online] Available at: https://search.findmypast.co.uk/record?id=GBC%2F1861%2F4216%2F00306A&parentid=GBC%2F1861%2F0020944287 [Accessed 25 Feb. 2020].