Early life

John Lynch was born in Cork around 1831. Ireland then was a land of famine and internal strife, the end of the Napoleonic wars had rendered Cork Harbour a barren wasteland and the economic downturn had cut the price of produce, meaning none could earn from their labours enough to buy the bare necessities. The result was nothing short of mass poverty and unemployment. A year after Lynch’s birth, a massive epidemic in the form of cholera swept through the city[1]. In the first two weeks of the outbreak, 50 people became infected and over half died. The pace of disease did not slow until the next year, with hospitals full and the deaths so numerous that a “Superior General, Brother Louis Hoare, was seen carrying out corpses on his back”[2].

By late 1845, as Lynch would have undertaken his catholic confirmation, the world began to hear of a blight on the potato crop. With a population of over three million[3] and, the majority of those subsisting meagrely on potatoes and a little milk, the result could only be tragic. In the new year the scale of the damage was finally understood with over half of the year’s crop being unusable.

To mitigate this in some small way, a poor relief fund had been created. Unfortunately, contrary to the modern form of charity, the Victorian belief that interference would create dependency meant that any relief given, such as the provision of corn meal, had to be paid for. Jobs were created doing public works, to allow the poor to afford this alternative food source, but these paid less than a pittance so any relief was scant[4].

Whilst the hope was that the famine would last just one year, 1847 brought swarms of starving beggars from the country to the overcrowded workhouses and hospitals; after these filled, eventually to their deaths on the streets. So many died, that a new cemetery opened and the mass inhumations were so numerous, that often the earth did not fully cover the top layer of incumbents[5].

Throughout all of this, disease ran rampant through the remaining populace. Typhus, Yellow fever and the bloody Flux or bacillary dysentery were rife. Despite this volatile mix of various debilitating and terminal diseases, Lynch survived to the 1860s, to marry, be widowed and to maintain a job as a clerk.

After many years of struggle the ruling classes, the majority of who were English and Protestant, had instituted multiple harsh measures, from the suspension of the habeas Corpus Act to a curfew that, if broken, would be punished with transportation. To put that into perspective, up to a third of men on board hulks awaiting transportation died. The Irish considered the British to be purposefully ignoring the starvation as a way to wipe out the “Irish Problem”. The British saw it differently, with one lieutenant quoted as saying “Governing Paddy has never been a hopeful or pleasant task, but it is a duty which Englishmen must perform as best they can[6]”.

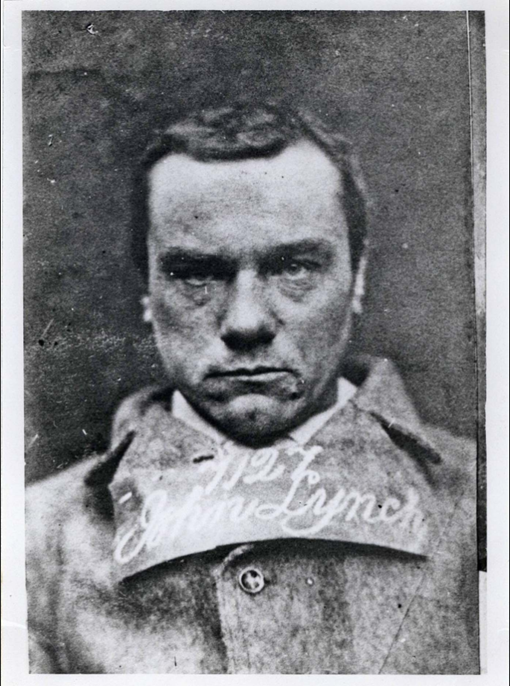

In this harsh and overwhelming environment, many men resolved to create a self-governing Republic, an Ireland of their own: in their words, God save the Green. At this point John Lynch enters the frame as a possible central player and agitator for an independent Ireland. He was friends with republicans and members of the Fenian Brotherhood and had ties to the Fenian Newspaper “Irish People” that ran for two years between 1863 and 1865. But was he actually plotting against the government or was it just a terrible mix up?

The Crime

The British were scared. The last thing they needed was for French republicanism to spread after the second revolution in 1848. The ruling elite had seen,in some cases experienced first hand, what an angry populace could achieve. The government realised that hanging the ringleaders, the usual reaction to treason, would cause more unrest. So in 1848, the Treason-Felony Act was passed allowing for a prison sentence rather than hanging for “minor” treason, and less of a requirement for such trivial things as evidence[7]. Not only were there laws curtailing the Irish, in the 1860s the British government resorted to sending in a spy, to discover how deep the insurgency had spread.

A man named Pierce Nagle, a British informer, gained employment at the “Irish People” paper and, along with local detectives, uncovered a money trail though the Rothschild banks backing the Fenian Movement[8]. Whilst this was happening, Daniel Ryan, head of the G Division of police at Dublin Castle, claimed that many men had been seen practicing with rifles ready for an open insurrection. On September 15th 1865, the office of Irish People was raided and multiple men were arrested[9]; they were amongst others, Charles Kickham the blind author, O’Donovan Rossa, latterly a famed memoir writer and John Lynch.

John Lynch, already succumbing to consumption, despite this was put to trial and sentenced as an able-bodied man on the word of a witness. A witness who had stated boldly that the men in the dock (one incapacitated from severe spinal curvature, another by blindness, and one by tuberculosis) had been practicing with rifles at the house of a brotherhood member and were planning to overthrow the British government.

Whilst for many of the others tried that day, there was evidence aplenty, letters to the American Branch of the Fenian movement, a supposed plot foiled by Dublin Castle’s finest and the funds transferred from America: for Lynch, there was little. Indeed, there was only a casual association with the other defendants and a few letters to a sweetheart, Bridget Noonan, which, although inflammatory and hinting at a republican spirit, did not implicate him in treason[10]. The letter said:

“Gladly indeed would I perish, could I only die in the arms of victory, with the green flag flowing proudly in the breeze and England’s hated, accursed felon rag going down into the nearest dunghill. Should we fail, the scaffold and the convict ship will make short work of us. What of that? The consciousness of suffering in a great and noble cause, to which every age has given its heroes, its martyrs and its saints . . . will console all true Irishmen in the hour of trial.”

The Jury, despite being called in a catholic country, was protestant at a count of 8 to 1. This was clearly an instance of jury bias and of the so named rebels, all were found guilty of Felony Treason and sentenced to Penal Servitude.

John’s speech at his conviction was simple but powerful:

“I will say in a very few words, my lords. I know it would be only a waste of public time if I entered into any explanations of my political opinions; opinions which I know are shared by a vast majority of my fellow countrymen. Standing here as I do will be to them the surest proof of my sincerity and honesty. With reference to the statement, all I have to say is, and I say it honestly and solemnly, that I never attended a meeting at Geary’s, that I never exercised with a rifle there, that I never learned the use of a rifle, nor did any of the other things he swore to. With respect to my opinions on British rule in this country…“

Here he was interrupted by the judge not wanting any protestations of his politics and resumed:

“If having served my country honestly and sincerely is treason, I am not ashamed of it. I am now prepared to receive any punishment British Law can inflict on me[11].“

He was sentenced to Ten Years for Felony Treason.

Prison

Lynch spent his first few months of interment at Mountjoy Prison,

“On the 13th Jan 1866 at 5:30am, inmates were transmitted from Mountjoy prison under an escort of mounted police and a troop of the 10th Hussars. The travelled first by second class train carriage and then aboard a mail steamer, under the guard of the Royal Marines from the HMS Royal George[12].”

and then on to Pentonville, There he began to fade, in a rare moment he spoke to a fellow Fenian, a man named O’Donovan Rossa. Rossa bemoaned the state of Lynch’s health and lynch confirmed “The cold is Killing me”. Less than a month later, in April of 1866, Lynch was removed to Woking Prison to join one of his dock mates Brian Dillon.

Lynch’s health was so poor that he remained in the hospital wing, under the care of inmate nurses and the chief medical officer John Campbell. Campbell was as much at a loss with TB as many other doctors of the time and may have through his ministrations, caused the disease to spread further.

Lynch would have been given the invalid diet; milk, fats, tea, some mutton and beer if he could take it, all fed to him by an inmate nurse. The chaplain, visiting intermittently, and Campbell nipping in and out to make an appearance once a day.

John lynch was too weak to work as a tailor[13] as he had done in his previous prisons, indeed, he was so weak that he would never leave that hospital wing alive[14].

Aftermath

John Lynch died in Woking on the 2nd of June 1866[15]. Over the next two years, 9 more of his fellow Fenian defendants would pass through the 18ft gates of Woking, but unlike Lynch they would be leaving alive.

Lynch was buried in Brookwood Cemetery[16], in an unmarked grave, in the unconsecrated ground of the non-conformist pauper plots.

There is now a plaque to him at Brookwood, not over his grave as no-one knows exactly where that is, but a visual reminder that he had lived briefly and died in Woking. There is another plaque to him also in Cork, next to the raided headquarters of the Irish People Magazine.

His death was a turning point, a rallying cry for many disenfranchised Irish and in 1867, a further uprising would take place followed by bombs in London and an attack on a prison van in Manchester. The prisons themselves were forced to undertake a review of how they had treated inmates, as the prisoners themselves, an incredibly literate group, wrote and shared widely shocking tales of abuse. Atrocities such as being forced to strip naked daily, poor food rations and punishments that were meted out to them alone and not other prisoners.

The review showed no poor practice on the part of the government, which is unsurprising as it was sanctioned and carried out by British protestant peers after all. Yet there remains reasonable doubt as to whether John Lynch’s death was caused solely by tuberculosis, or if the purported poor treatment received in prison, hastened his end.

[1] ‘Cork In The 19Th Century | Cork Past & Present’ (Corkpastandpresent.ie) <http://www.corkpastandpresent.ie/history/historyofcorkcity/1700-1900/corkinthe19thcentury/> accessed 22 September 2020

[2] John Casey, ‘Connecting The Edmund Rice Movement – Remembering The Cholera Epidemic Of 1832’ (Edmundrice.net) <http://www.edmundrice.net/2-uncategorised-sp-786/1541-remembering-the-cholera-epidemic-of-1832> accessed 7 October 2020.

[3] Ibid

[4] Ibid

[5] ibid

[6] Christopher Kissane, ‘“Governing Paddy Has Never Been A Hopeful Or A Pleasant Task”’ (The Irish Times, 2016) <https://www.irishtimes.com/culture/books/governing-paddy-has-never-been-a-hopeful-or-a-pleasant-task-1.2859627> accessed 5 October 2020.

[7] Frank Rynne, ‘Focus On The Fenians: The Irish People Trials, November 1865–January 1866’ (History Ireland, 2006) <https://www.historyireland.com/18th-19th-century-history/focus-on-the-fenians-the-irish-people-trials-november-1865-january-1866/> accessed 5 October 2020.

[8] Ibid

[9] Stair hÉireann and Stair hÉireann, ‘1865 – Police Raid And Close The Irish People Offices; Rossa, Luby And O’Leary Are Arrested.’ (Stair na hÉireann | History of Ireland) <https://stairnaheireann.net/2016/09/15/1865-police-raid-and-close-the-irish-people-offices-rossa-luby-and-oleary-are-arrested/> accessed 5 October 2020.

[10] ‘An Irishman’s Diary’ (The Irish Times, 2003) <https://www.irishtimes.com/opinion/an-irishman-s-diary-1.357912> accessed 5 October 2020

[11] ‘Southern Reporter And Cork Commercial Courier’ (Britishnewspaperarchive.co.uk, 1865) <https://www.britishnewspaperarchive.co.uk/viewer/bl/0000876/18651220/055/0003> accessed 7 October 2020.

[12] ‘Documenting Ireland: Parliament, People And Migration’ (Dippam.ac.uk, 1866) <http://www.dippam.ac.uk/ied/records/42959> accessed 24 September 2020

[13] Prison System, ‘John Lynch’ (Government Prison 1865) <https://search.findmypast.co.uk/record?id=TNA%2FCCC%2FPCOM5%2F039%2F00004&parentid=TNA%2FCCC%2F2F%2FPCOM5%2F00000987> accessed 8 October 2020.

[14] ibid

[15] ibid

[16] ‘John Lynch’ (Tbcs.org.uk, 2017) <https://www.tbcs.org.uk/necropolis_notables/john_lynch.html> accessed 8 October 2020.