“Get up Mrs Pyles, there’s a dead woman in my house!”

Summary

Emery Spriggs, far from being a west country curse, is the name of one of Woking Prison’s most notorious inmates. A publican, born and bred in the picturesque village of Westbourne, West Sussex, he was for all intents and purposes a much-liked local man. His wife, Rebecca Spriggs, too was equally well liked and respected, despite a few hang-ups and hangovers. Which makes this case all the stranger, for the events that transpired one terrible January morning in 1854.

Early Life

Emery Spriggs was the 6th child of Henry and Elizabeth Spriggs (nee Mitchell), born sometime in 1803 and baptised on the 4th December of that same year at the parish church, St John’s in Westbourne[1]. The Spriggs’ had laid deep roots in this town where, for 2 generations at least, the family had lived, loved and died. Who can blame them as, according to the 1851 ‘The Six Home Counties Post Office Directory’[2], Westbourne was:

‘a large parish, and gives name to a Hundred and Union in the area of Chichester, 7 miles from that city, and within a short distance of Emsworth harbour… its area is 4,230 acres; population in 1841, was 2,093; assessed to the income tax at 10,111 pounds. The village, formerly a trading town, is of considerable size, pleasingly situated, though on a low site. It was formerly the residence of the Freeland family, ancestors of the family now resident in Chichester. The Church, dedicated to St. John The Baptist, is a neat structure; the living is a rectory and vicarage, value 425 per anum, the former a sinecure; the deanery of Boxgrove. The rector and vicar is the Rev. Henry Newland, MA. Here is a National school for 80 boys and 80 girls. The Union poor house is also in this parish.’

On the 18th May 1825, at the aforementioned parish church, Emery married Rebecca Tumbler and less than a year later, she bore him a daughter, Elizabeth[3]. Their daughter lived with them for several years, but in 1847 she was married and by 1851 was living in Hampshire. Throughout the census’ of 1841 and 1851, the couple resided in the pub in which Emery worked, The Cricketers, and were frequently visited by other family members: at the former census by his sister and niece, Elizabeth and Louise Spriggs, and at the latter by his widowed uncle, John[4].

The pub was a real hub of local life, both for the Spriggs family but also the community at large, proving to be a popular venue for drinks, events and, eventually, murder.

The Crime

Emery had been under a great deal of pressure. The application for an alcohol licence for his pub was opposed and, on the 15th September 1853, denied by the Reverend Newland and Churchwardens of Westbourne[5]. Add to this his gout, likely exacerbated by a ready access and excess of alcohol, had begun to flair to such an extent that he started to experience ‘delirium’: a medically attested state characterised by confusion, hallucination and aggression. Combine this with his wife’s severe alcoholism and we have a cocktail for disaster.

The night of the 12th January 1854 started well. A ball was thrown for 19 couples (or 50-60 persons) of a benefit society, the ancient order of Foresters, and drink ‘flowed freely’ until a late hour. According to the North Devon Journal Emery in particular, was very gay and ‘exhibited much hilarity and activity’[6]. His wife also was in good spirits and later reports state that she fell over a number of times due to intoxication, had ‘said a few words to him’ and taunted him about having a ‘fancy woman’. Although, in contrast to the accepted events of the night, one of the daughters of a later witness, Catherine Pyles/Pile/Piles, stated that both the Spriggs’ were upstairs for much of the night and that their doorkeeper, Mr. Goddard, attended to the guests[7]. Either way, as the party wound down and only the Spriggs’ remained, a final, bloody act took place.

No-one knows for sure what triggered Emery to kill his wife. Whether it was because of, as testified by his defence, gout delirium or due to his wife’s antics. What is certain that just before 5am, Emery fired his shotgun at Rebecca Spriggs. The bullet went straight through her skull, spattering the wall with gore killing her instantly as she fell in the passageway beside the front door of the pub.

Emery, far from hiding his crime, roused his neighbour, Mrs Pyles, from the adjoining cottage and said to her “Get up, Mrs. Pyles, there is a dead woman in the house”[8]. She immediately responded “Oh Spriggs, don’t say that!” before coming over and seeing the grisly spectacle before her. Spriggs called two further women and asked them to sort out his “dear wife, and [do] their duty by her”[9]: their duty in this instance meant removing her from the passageway and tidying up the scene. Ann Hedger was one of the women and claimed, in court, that he confided in her that “no tongue can tell my trouble”[10]. Before they could complete the task of moving the body, he collapsed on the body and exclaimed words of such pity, that they would save him from the noose.

‘Oh, Becky, Becky, I always loved ye, and I love ye now!”[11]

As the body was removed upstairs, Emery sought out his friend and doorkeeper, Mr. Goddard, and told him of the crime.

“I had a scuffle with my wife, but I gained the victory. I shot her with the right-hand barrel, and that’s the finger”, he said pointing with the forefinger of the right hand, “that did it”[12].

Goddard sent for a Constable, who sent for a surgeon and Spriggs was taken into custody at Petworth Jail. The witness descriptions and coroner’s reports are harrowing, going into great detail about the extent of the wounds and the state of the crime scene; the only saving grace being that she died instantly with ‘barely a gasp’.

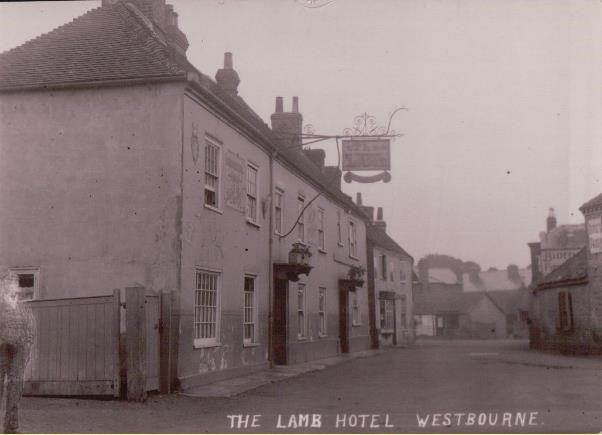

Inquest was held at The Lamb Inn, a rival pub in Westbourne. Source: https://westbournevillage.org/

During the trial, Goddard spoke about the night in question, fainting in intervals, saying he “had known the prisoner and the deceased for 20 years. That formerly they lived very happily together, but of late the deceased had become addicted to drinking, and this had caused differences between them. The prisoner suffered a good deal from gout. During the evening he had requested him particularly to keep his wife from getting at the spirits, but she had done so without his knowledge. The hands of the deceased were very dirty, and her nose appeared to be cut, as though she bad been falling about. They were very good friends when he left them. The prisoner was suffering from gout at the time this occurrence took place, and he had his gouty slippers on.”[13]

The gout defence was accepted and the crime itself only slightly mitigated by his tender actions post having killed her. At the Lewes Assizes on the 3rd March 1854, Emery aged 50 and described by court reporters as a ‘respectable looking man’ was sentenced to be transported for life[14].

Imprisonment

During the trial and for four months after, Emery was held at Petworth Gaol, a prison renowned for its liberal use of punishment and heartless governance. At Petworth he wiled away his time in separation, picking Oakum and keeping his nose out of trouble. Despite his ‘Good’ conduct, the Governor John Mance wrote on his record that his mind was ‘of a callous and reserved temper and not sufficiently aware of his situation’[15]. Whilst his lack of awareness of the ‘situation’ is borne out by the witness statements of his behaviour during the manslaughter, words like ‘madman’, ‘delirium’ and ‘out of his mind’, the accusation of callousness, as will be presently seen, is not proved in any way during his time in prison.

On the 17th July 1854, Emery was moved from Petworth to Millbank, where his behaviour was described as exemplary and that even at the age of 50, had made fair progress in schooling. From Millbank to Dartmoor on the 29th November 1854, from Dartmoor to the hulk Stirling Castle on the 25thAugust 1855 and to the Defence on the 28th October 1855[16]. His behaviour at all was Good and his schooling fair, indeed he seemed to thrive in this atmosphere, until the Defence burnt down on the 14th July 1857[17]. That same day he was taken back to Millbank, with all of the other rescued invalid inmates, then to Lewes 2 months later, before finally ending up at Woking Invalid Convict Prison on the 22nd March 1860[18]. His health had been worsening for a while, described at time as ‘delicate’, ‘rather delicate’ and infirm: Woking was the best place for him. Indeed, Emery was part of the first intake of invalided prisoners on the prison’s official opening day[19].

In the 7 years that Emery was at Woking, he never received a behaviour report worse than good and even received over 14 very goods in the extant surviving quarterly returns. Nor were the staff alone in recognising his virtue. Sometime early 1864 the home secretary received a letter requesting his release. The home secretary’s secretary, Mr Waddington, responded;

“Sir, I am advised by secretary Sir George Gray to acquaint you that he cannot authorize the release of the convict Emery Spriggs who was recommended for license in the lastly monthly list, as he is under life sentence. I am sir your obedient Servant”[20]

Again in 1864 another letter was sent, the response unchanged:

“Secretary Sir George Gray having considered the case of the convict named in the margin [Emery Spriggs], now under life sentence in Woking Prison I am directed to acquaint you that he cannot sanction the release on license of this man at present.”[21]

And again in 1866, from George Grey’s new secretary, Sir T. G. Baring:

“Secretary Sir G. Grey having considered the case of the convict in the margin [Emery Spriggs], now under life sentence in Woking Prison; I am directed to acquaint you that he cannot advise Her Majesty to grant a license to the same.”[22]

Try as the they might however, the government had no excuse to keep him imprisoned in perpetuity and so on the 27th February 1867, a license was created to allow his release. Nine days later Emery was at liberty, his pockets stuffed with £20 17s and 4 1/2d, money accrued from gainful employment whilst incarcerated: not a single penny deducted for bad behaviour or misconduct[23].

Emery Spriggs, in the end, only served 17 years for the unlawful murder of his wife.

Aftermath

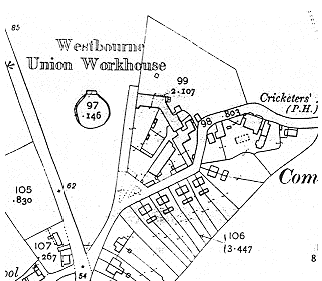

After his release, Emery returned to the village of his birth, where the true punishment was enacted. There is no record of how awkward it must’ve been for a former figurehead, returning as a pariah to the ruins enacted at his own hands, but it must’ve been difficult indeed. In 1871 Emery Spriggs, aged 67, was now working as a general labourer and lodging with the Woods family at North Street, Westbourne[24]. From the day of his release to the day of his death in 1875, Emery stayed with friends, working menial jobs to earn his keep before finally ending up in the workhouse; a place overlooking the pub and memories of a love and life he cut short and once knew[25].

Trivia

Colonel Wyndham, Governor of Woking Invalid Convict Prison, was a major landholder in Wetsbourne and thus a former neighbour of Emery before his incarceration.

In the 1980’s ‘The Ballad of Emery Spriggs’ was written*.

*If you have any information on the Ballad or know of a recording, could you please email us at institutionalhistory@gmail.com

[1] ‘England, Select Births And Christenings, 1538-1975’ (Ancestry, 2020) <https://search.ancestry.com/cgi-bin/sse.dll?indiv=1&dbid=9841&h=155066254&ssrc=pt&tid=65869048&pid=422157183840&usePUB=true> accessed 9 March 2020.

[2] ‘The Six Home Counties Post Office Directory 1851’ (Ancestry, 2020) <https://www.ancestry.com/interactive/1547/GBM001-0004-00138?pid=881779&backurl=https://search.ancestry.com/cgi-bin/sse.dll?indiv%3D1%26dbid%3D1547%26h%3D881779%26tid%3D%26pid%3D%26usePUB%3Dtrue%26_phsrc%3DMzR819%26_phstart%3DsuccessSource&treeid=&personid=&hintid=&usePUB=true&_phsrc=MzR819&_phstart=successSource&usePUBJs=true#?imageId=GBM001-0004-00137> accessed 9 March 2020.

[3] ‘England, Select Marriages, 1538–1973’ (Ancestry, 2020) <https://search.ancestry.com/cgi-bin/sse.dll?indiv=1&dbid=9852&h=22532980&ssrc=pt&tid=79090688&pid=46581782324&usePUB=true> accessed 9 March 2020.

[4] ‘1851 Census’ (Ancestry, 2020) <https://search.ancestry.com/cgi-bin/sse.dll?dbid=8860&h=3375833&indiv=try&o_vc=Record:OtherRecord&rhSource=7619> accessed 9 March 2020.

[5] <https://www.britishnewspaperarchive.co.uk/viewer/bl/0000938/18530915/108/0007> accessed 9 March 2020.

[6] (2020) <https://www.britishnewspaperarchive.co.uk/viewer/bl/0001702/18540113/073/0006> accessed 9 March 2020.

[7] ‘Murder At The Cricketers 1854’ (Djbryant.co.uk, 2020) <http://www.djbryant.co.uk/westbourne-yesteryear/murder-crickets.html> accessed 9 March 2020.

[8]‘Register | British Newspaper Archive’ (Britishnewspaperarchive.co.uk, 2020) <https://www.britishnewspaperarchive.co.uk/viewer/bl/0001098/18540321/088/0010> accessed 9 March 2020.

[9] Ibid.

[10] Ibid.

[11] Ibid.

[12] Ibid.

[13] Ibid.

[14] Ibid.

[15] ‘License’ (Findmypast, 2020) <https://search.findmypast.co.uk/record?id=tna%2fccc%2fpcom3%2f217%2f00427&parentid=tna%2fccc%2f2b%2fpcom3%2f01467673> accessed 9 March 2020.

[16] Ibid.

[17] Ibid.

[18] Ibid.

[19] Ibid.

[20] ‘Letter From Waddington’ (Findmypast, 2020) <https://search.findmypast.co.uk/record?id=tna%2fccc%2fpcom3%2f217%2f00432&parentid=tna%2fccc%2f2b%2fpcom3%2f01467673> accessed 9 March 2020.

[21] Letter From Waddington 2′ (Findmypast, 2020) <https://search.findmypast.co.uk/record?id=tna%2fccc%2fpcom3%2f217%2f00434&parentid=tna%2fccc%2f2b%2fpcom3%2f01467673> accessed 9 March 2020.

[22] ‘Extract From The B Letter’ (Findmypast, 2020) <https://search.findmypast.co.uk/record?id=tna%2fccc%2fpcom3%2f217%2f00433&parentid=tna%2fccc%2f2b%2fpcom3%2f01467673> accessed 9 March 2020.

[23] ‘Marks And Money’ (Findmypast, 2020) <https://search.findmypast.co.uk/record?id=tna%2fccc%2fpcom3%2f217%2f00418&parentid=tna%2fccc%2f2b%2fpcom3%2f01467673> accessed 9 March 2020.

[24] ‘1871 Census’ (Ancestry, 2020) <https://search.ancestry.com/cgi-bin/sse.dll?dbid=7619&h=27275894&indiv=try&o_vc=Record:OtherRecord&rhSource=8860> accessed 9 March 2020.

[25] ‘Murder At The Cricketers 1854’ (Djbryant.co.uk, 2020) <http://www.djbryant.co.uk/westbourne-yesteryear/murder-crickets.html> accessed 9 March 2020.