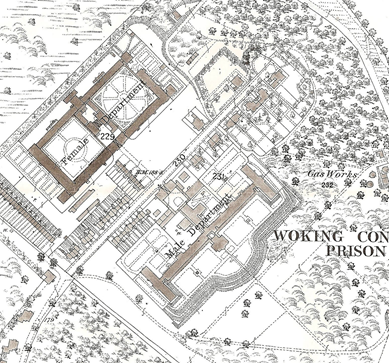

Woking Female Prison began construction in 1867 utilising convict labour from the Male Invalid Prison on the site in Knaphill. It was the first purpose-built female prison in the UK[1]. It was constructed with the help of the male convicts serving their sentence in Woking Invalid Prison just next door.[2] Upon opening Woking Female Convict Prison received approximately 100 female inmates from Parkhurst Prison on the Isle of Wight[3]. Operating for a total of 26 years, the prison was the first of its kind and specifically tailored to the redemption of female criminals until its closure in 1895 when the remaining convicts were transferred to Holloway Prison and the buildings were handed over to the war office – serving as a military hospital during WWI[4].

Whilst the original expectation was for the prison to hold up to 700 female inmates on the 7 and a half acres it occupied, it was reported to have often exceeded this[5], although by the late 1880s it held as few as 300. Like the men’s prison, this prison was aimed mostly at the elderly, or infirm who could not be expected to undertake the standard heavy labour required of inmates.

Those who were convicted for the first time wore a red star pinned to the sleeve of their uniform dresses to denote “Star Class” prisoners[6]. Star Class prisoners had access to greater privileges, extra time amongst the public on works, or less solitary workloads, and a better diet.

The Mosaics

Woking Female Prison, uniquely, became renowned for the production of mosaics. The female inmates, much the same as male inmates, were put to work within the prisons. However, unlike the arduous, physical work that male convicts were subjected to, the female prisoners at Woking had the opportunity to earn up to 1 shilling a day for their mosaic work[7].The inmates were given off-cuts of marble which they then cut down to size and arranged in a pattern to create the mosaics, some of which went on to be exhibited at the 1872 International Exhibition of the Fine Arts and Industry at the Royal Albert Hall. It is even believed that some of the flooring in St Paul’s Cathedral is courtesy of the labour of Woking’s female convicts[8].

The Experience of a Female Convict

Before Woking Female Prison, Victorian prisons were designed solely for male criminals, women were, at most, an afterthought.

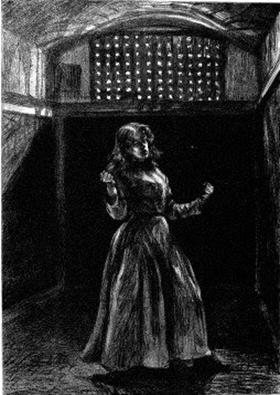

With the introduction of female prisons came a new system of rehabilitation tailored around the principals of domesticity and motherhood[9]. Unlike their male counterparts, female inmates were not thought to have the mental or physical capacity to carry out laborious outdoor work. As a result, they were often confined within the four walls of the prison all hours of the day[10].

Seen to be more social members of society, female convicts were kept in solitary confinement and intentionally deprived of conversation as a disciplinary tool[11]. Their roles within the prisons, other than mosaic work in the case of Woking, involved working in the laundrettes and kitchens. In Victorian England, women were expected to play a moralising role within society, female criminals, particularly those who committed ‘crimes of morality’ such as prostitution, were seen to have deviated from their duties and therefore their confinement aimed to realign them with their domestic purpose. There was a three-stage procedure in the conviction process of a female criminal: separate confinement usually at Millbank prison, ‘public works’ typically at Brixton or Woking prison and finally release on license[12].

Prisoners You Might Know

Florence Maybrick, American socialite and “media celebrity”, served a sentence in Woking’s Female Prison after being accused of the murder of her husband, James Maybrick[13]. Her husband, who was 23 years her senior, was thought to have been poisoned by Florence in 1889 when the post-mortem revealed traces of arsenic within his bloodstream. Upon her initial arrest, Florence was sentenced to death, however after an appeal this was changed to life imprisonment. Although the evidence of Florence having administered the poison was strong, it was revealed that this was unlikely to have been the direct cause of his death[14].

Constance Emily Kent, notorious for the Road Hill House murder in 1860, served some of her life sentence in Woking Female Convict Prison and had worked on the mosaics. Convicted of the murder of her 3-year-old half-brother, Kent was initially sentenced to death in 1865 but, as a result of her youth – being only 16 years of age – this was altered to a life sentence of which she served 20 years[15].

Lucy Lowe, also known as Lucy Ellis, was convicted of murdering her 21-days-old baby in 1876. Records indicate that in 1881, Lucy was an inmate at Woking Female Convict Prison.

[1] Prison History, ‘Woking Female Prison’, [online], available at https://www.prisonhistory.org/prison/woking-female-prison/ [accessed on 29th July 2020]

[2] Wakeford, Iain, ‘1872 – Welcome to the world of the women prisoners of Woking’, Woking History, 2015

[3] Woking Prison, ‘Woking Invalid Convict Prison’, Blogspot, 2009

[4] Prison History, ‘Woking Female Prison’

[5] Aberdeen Press and Journal, ‘The Female Prison at Woking”, 1889, [online], available at https://www.britishnewspaperarchive.co.uk/viewer/bl/0000032/18890906/007/0003

[6] Aberdeen Press and Journal, ‘A Description of Woking Female Prison”, 1889, [online], available at https://www.britishnewspaperarchive.co.uk/viewer/bl/0000575/18891002/084/0005

[7] Wakeford, ‘1872 – Welcome to the world of the women prisoners of Woking’

[8] Ibid.

[9] Bennett, Rachel, Catherine Cox, Hilary Marland, ‘The Treatment of Women in Prison in the 19th Century’, Brewminate: A Bold Blend of News and Ideas, 2018

[10] Zedner, Lucia, ‘Women, Crime and Penal Responses: A Historical Account’, Crime and Justice, Vol, 14, 1991, pp. 307-362

[11] Bennett, Rachel, ‘Bad for the Health of the Body, Worse for the Health of the Mind: Female Responses to Imprisonment in England, 1853-1869’, Social History of Medicine, Vol. 0, No. 0, pp.1-21

[12] Johnston, Helen, ‘Imprisoned Mothers in Victorian England, 1853-1900: Motherhood, Identity and the Convicr Prison’, Criminology & Criminal Justice: An International Journal, Vol. 19, No. 2, 2019

[13] Birch, Dinah, ‘Did she kill him? Review – A Victorian Scandal of Sex and Poisoning’, The Guardian, Feb 2014

[14] Ibid.

[15] Murdopedia, ‘Constance Emily Kent’, [online] available at https://murdopedia.org/female.K/k/kent-constance.htm, [accessed on 1st August 2020]

Written by Danielle Yates