Introduction

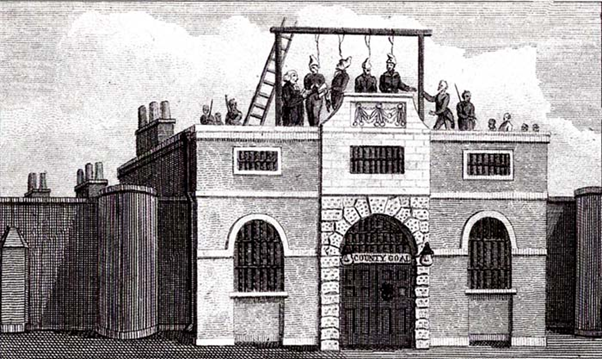

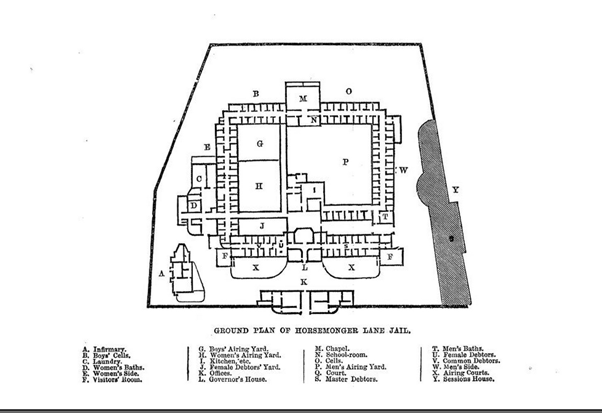

The gaol at Horsemonger Lane, also known as Surrey County Gaol or New Gaol, was built in the late 1790s in Southwark, south London. It was designed by the Surrey surveyor George Gwilt and was in continuous use for nearly 100 years. Built adjacent to the Inner London Court House as a replacement to a much earlier gaol close to the site called Borough Gaol[1]. Horsemonger Lane was stated to be the largest prisons in the country at one time housing as many as 300 inmates: both male and female. Quadrangular in shape and three stories tall, it featured three wings for different classes of criminals and a fourth for debtors.

The prison had a constant turnover of temporary residents awaiting trial and during 1837 it was recorded that some 1,300 debtors and 2,506 criminals were held there. It was also a site of execution for more than 130 men and women: this initially took place on the roof of the gatehouse when executions were held publicly but was later moved inside the prison after 1868[2]. In the mid-1800s, the prison was renamed the Surrey County Gaol or New Gaol. Horsemonger Lane was later renamed Union Road before being changed again to Harper Road, the name it still holds[3].

Background & History of the Prison

In Elizabethan times this area of Southwark was infamous for disreputable activities, such as prostitution, bear-baiting and was a haven for shady characters seeking to evade the law. It was also a centre for theatre, which no doubt added to the crime rate as crowds poured in. Later, the Newington Causeway at the Elephant and Castle would become the base for several small gaols, such as The White Lion Gaol, which were eventually replaced by a much larger one well away from “respectable” Whitehall; Horsemonger Lane Gaol. The prison was visited by multiple contemporary celebrities from Lord Byron to Charles Dickens[4].

Henry Mayhew, the famed chronicler of the poor reported the prison thus:

“It is enclosed within a dingy brick wall, which almost screens it from the public eye. We enter the gateway of the flat-roofed building at the entrance of the prison, on one side of which is the governor’s office, and an apartment occupied by the gate-warder, and on the other is a staircase leading up to a gloomy chamber, containing the scaffold on which many a wretched criminal has been consigned to public execution[5].”

Inmates held for trial and debtors had some freedom in terms of discussion with other inmates and could purchase their own meals and beer from local inns. However this proved to be a double-edged sword, as inmates were not allowed to supplement the prison provision, instead they either had to accept the food and clothing from the prison or pay for everything out of their own pocket.

Those convicted of their crimes and held at Horsemonger lane had a different experience in other ways. They had no ability to improve their condition, they were expected to wear prison garb and eat prison food and were held in strict seclusion, with individual walled seats in the chapel, meals taken in individual cells and segregation of male and female inmates[6].

Famous Prisoners

Horsemonger Lane Gaol not only housed many famous faces of the time but also staged over a hundred executions. One such criminal was Captain Henry Nichols, who was sentenced to die for sodomy and other “abominable” crimes.

“EXECUTION. Yesterday morning HENRY NICHOLL, late Captain on the retired list of the 14th regiment of infantry, was executed at Horsemonger lane gaol. He was tried and found guilty of an abominable offence, at the late Surrey Assizes, and in the course of the trial it was proved in evidence, that he belonged to a gang of which BEAUCLERK, who. it may be recollected. committed suicide some time since in the county gaol, formed one of the parties. NICHOLL had entered the army at an early period of life, and formerly belonged to the 72d, from which he exchanged into the 14th Foot, and with this regiment had seen a good deal of service abroad. The night previous to his execution lie slept soundly for some hours, and on awakening and inquiring the hour appeared anxious for the arrival of the Sheriff and the executioner. At nine o’clock precisely he was led from his cell to the place of execution, which is immediately over the entrance into the gaol, and after a short time spent in prayer the drop fell, and he soon ceased to exist. A large concourse of people assembled to witness the execution[7].”

In 1861, the penalty for sodomy was reduced to life imprisonment but that change came almost thirty years after Henry Nichols was executed.

Other famous inmates included writer and intellectual Leigh Hunt (imprisoned for two years for libel against the Prince Regent – he met Lord Byron for the first time during his unexpected sojourn in the gaol) as well as Colonel Edward Despard, an Irishman found guilty of high treason and, along with six others, sentenced to be hanged, drawn and quartered. This was late commuted to hanging and beheading which was carried out on 21st February 1803.

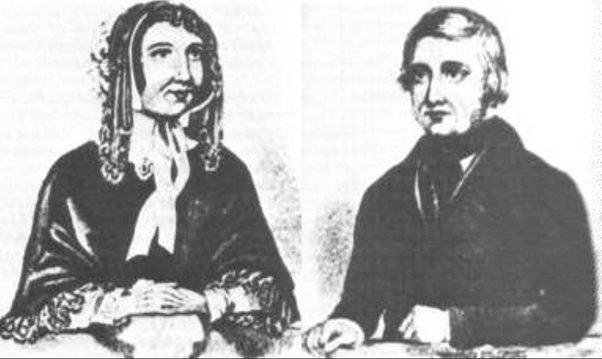

Among the most infamous executions at Horsemonger Gaol, was that of Frederick and Maria Manning, a murderous husband and wife.

Theirs was a grisly crime that shocked Victorian England and would later become known as the ‘Bermondsey Horror[8].’

On August 9th 1849, a 50-year-old Irish customs officer called Patrick O’Connor sat down to have dinner in Bermondsey’s Miniver Place, off Weston Street. His hosts were swiss born Maria Manning nee de Roux, who was once a ladies’ maid, and her husband Frederick, a disgraced guard on the Great Western Railway[9].

Maria had met O’Connor on a boat-trip to Boulogne with Lady Blantyre, her employer at the time. She was charmed by O’Connor, and suggested they meet up next time they both were in London. She began a relationship with him, but at the same time met Frederick, whom she married, believing him to be heir to a fortune. This proved to be untrue as Frederick had no money, and had even been discharged from his post at the station, as he was thought to be in league with the robbers who had absconded with thousands of pounds in railway property[10].

She continued to dally with O’Connor, apparently with her husband’s knowledge and consent. O’Connor became a frequent visitor at their home, and there was even talk of his living with the couple as a lodger. This did not come to pass and the Manning’s, finding themselves nearing poverty again, made disturbing plans. O’Connor had wealth in abundance, he owned stocks and worked part time as a money lender[11]. In July of 1849 the couple ordered caustic lime and on the 8th of August, the same day a new shovel had been delivered to their home, Maria sent Patrick an invitation to dinner[12]. Their scheme was thwarted when O’Connor brought a friend, Walshe, to supper with him, a supper he could not eat as he became strangely faint.

He was invited back the next day, supposedly so the trio could be more intimate together, but by evening he was dead and buried in a pre-dug grave under the kitchen floor. Shot by Maria, then finished by Frederick Manning battering him over the head with a ripping chisel.

The duo parted company after divesting Patrick’s home of his belongings, Maria heading to Edinburgh and Frederick to Jersey. The home was only searched when it became apparent that they had no intention of returning.

Patrick O’Connor was later found alongside Maria’s bloody dress by police, hidden under the flagstones of the kitchen which a sharp eyed officer noticed to be freshly lain. The couple were found that same month, living under assumed names.

During the Old Bailey trial in October, both husband and wife tried to blame the other. Mrs Manning was accused of greed, killing her lover for his money. Mr Manning was accused of acting out of jealousy, unable to deal with the man his wife was sleeping with.

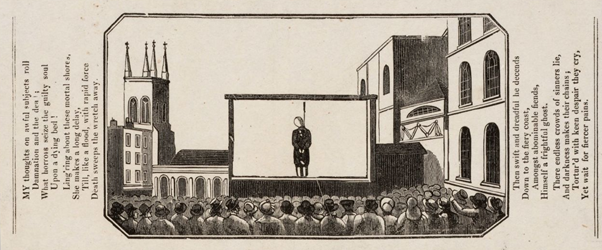

The jury charged them both with murder and they were sentenced to be hanged at Horsemonger Lane Gaol. On the 13th November 1849 the execution was watched by a crowd of between 30,000 to 50,000 people.

It attracted comment from the era’s leading chroniclers and the Mannings went down in the history books as the first husband-and-wife duo hanged together in England in over a century.

Among those in the crowd was none other than Charles Dickens, who was disgusted by what he saw:

“I was a witness of the execution at Horsemonger lane this morning,” he wrote in a letter to The Times, continuing, “I believe that a sight so inconceivably awful as the wickedness and levity of the immense crowd collected at that execution this morning could be imagined by no man.[13]”

Dickens was among those who campaigned against public hangings, which were eventually abolished in 1868. He later based one of his characters, Mademoiselle Hortense, Lady Dedlock’s maid in Bleak House, on Maria Manning.

The Prison today

Horsemonger Lane Gaol was demolished in 1881 and replaced by a public park, Newington Gardens, which was opened by Mrs Gladstone in 1884 and is publicly accessible today. The site is still home to some reminders of the prison, not least in those inmates buried within the walls of gaol and now, the park.

[1] ‘Southwark Prisons’, in Survey of London: Volume 25, St George’s Fields (The Parishes of St. George the Martyr Southwark and St. Mary Newington), ed. Ida Darlington (London, 1955), pp. 9-21. British History Online http://www.british-history.ac.uk/survey-london/vol25/pp9-21 [accessed 21 April 2021].

[2] Clarke, R., 1995. Horsemonger Lane. [online] Capitalpunishmentuk.org. Available at: <http://www.capitalpunishmentuk.org/horsemon.html> [Accessed 23 April 2021].

[3] Ibid 1

[4] Ibid 1

[5] Mayhew, H., 1862. Criminal Prisions of London and Scenes of Prison Life. London: Griffin, Bohn, and Company, pp.623-625.

[6] Ibid 5

[7] Sun (London), 1833. Execution. [online] p.3. Available at: <https://www.britishnewspaperarchive.co.uk/viewer/bl/0002194/18330813/035/0003> [Accessed 26 April 2021].

[8] U.osu.edu. 2019. The Bermondsey Horror | Undergraduate Research: Portrayal of the Female Offender. [online] Available at: <https://u.osu.edu/kneffler2research/2019/06/15/the-bermondsey-horror/> [Accessed 26 April 2021].

[9] 1849. The Bermondsey Murder: A Full Report of the Trial of Frederick George Manning and Maria Manning,. London: Royal College of Physicians.

[10] Ibid9

[11] Blanco, J., n.d. Maria Manning | Murderpedia, the encyclopedia of murderers. [online] Murderpedia.org. Available at: <https://murderpedia.org/female.M/m/manning-maria.htm> [Accessed 26 April 2021].

[12] 1849. The Bermondsey Murder: A Full Report of the Trial of Frederick George Manning and Maria Manning,. London: Royal College of Physicians.

[13] Perdue, D., n.d. The Charles Dickens Page – Dickens Witnesses Public Execution. [online] Charlesdickenspage.com. Available at: <https://www.charlesdickenspage.com/public-execution.html> [Accessed 26 April 2021].