Background Information

Clerkenwell House of Correction was opened in 1847, built on the site of two former prisons: Clerkenwell Bridewell and the New Prison. Also known as Clerkenwell Old Prison, Clerkenwell House of Detention and Middlesex House of Detention, the prison was located on St James’ Walk, in London’s central district of Farringdon[1]. By the 1840s New Prison was hideously overcrowded, with inmates being separated by lines on the floor and as many as 30 inmates to a room.

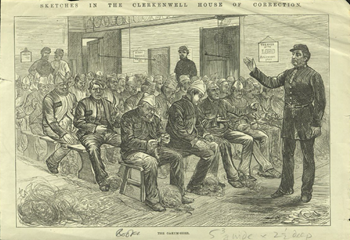

The House of Correction was built according to the contemporary Pentonville prison standards imposed by the Prison Act of 1839 which stated a preference for Victorian prisons to adopt the separate system[2]. Under this system, prisoners were kept in isolation from one another in separate cells[3]. Each cell contained a toilet and sink, although the architecture was considered to be cruder than that of Pentonville[4]. Despite being less aesthetically pleasing than other prisons, there was great technological sophistication here as a large air conditioning system drew heat from the basement through a series of vents, to warm the cells.

For this reason, Clerkenwell House of Correction was seen to symbolise a step forward in prison reform, following a more ‘commodious plan that treated inmates better than in previously constructed institutions such as Newgate[5]. One of the busiest prisons in London, Clerkenwell saw approximately 8,000 prisoners per annum. Those held in Clerkenwell House of Correction were inmates, male and female, awaiting trial for petty crimes at the Middlesex Sessions House; the nation’s largest courthouse after it opened in 1782[6]. As it was used to hold those arrested but not convicted, inmates were often allowed to wear their own clothes and food could be provided by friends or relatives if they had the means to do so[7]

Within forty years after opening, Clerkenwell House of Correction was demolished almost in its entirety. All that remained, the basements, were incorporated into the site’s next use as the Hugh Myddelton School in 1893[8].

Throughout World War II, the old basement was reopened for public use as air raid shelters.[9] In 1971, upon Hugh Myddelton School’s closure, the buildings were converted into a block of flats, which still stand today.

The Prison Layout

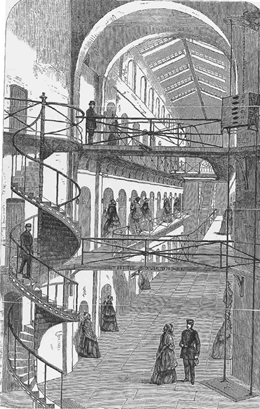

View along the north wing from the central hall

The prison’s building plans, designed by architect William Moseley, largely drew inspiration from Pentonville Prison which, also, adhered to the separate system[10]. At a total of three storeys high, Clerkenwell followed the traditional model of Victorian prisons: a central hall with wings radiating out of it, allowing for the separation of the sexes[11]. Each prison cell was equipped with its own water chamber, basin and a small window.[12] The three northern wings of the prison were strictly for male inmates, with the fourth wing incorporating offices, staffrooms, the chapel and other areas admissible for both sexes[13]. Prisoners were permitted to exercise in the yards that existed between the wings.

Throughout its four decades of operation, the prison saw a variety of architectural additions including an extension of the female wing, an extra storey added to each of the male wings and lengthening the boundary wall[14].

The Clerkenwell Explosion

Clerkenwell Prison is historically known for the infamous failed prison rescue attempt in 1867, later referred to as ‘The Clerkenwell Outrage.’ In December of 1867, the Irish Republican Brotherhood (IRB), colloquially known as the Fenians attempted to break out two of their members, Richard Burke and Joseph Casey. On the evening of the escape attempt, the Home Office received intelligence regarding the group’s plan to use gunpowder to blow up the exercise walls in the early hours of the following morning; there was an earlier failed attempt that day, when the gunpowder had failed to ignite.

A white ball was to be thrown into the air by the IRB to signal the plan’s commencement, according to the Dublin Metropolitan Police. Receiving this information in advance, the prison officers were all armed and the intended recues were moved to a high security cells to prevent their escape. At approximately 3.45am, the signal was given and a barrel of gunpowder was ignited alongside the prison walls causing an explosion which took the lives of at least six bystanders, and injured 50 more: some contemporary estimates reported double these figures[15]. In the aftermath, 60ft of the wall was damaged in the attempted, and houses nearby were almost destroyed. This attack, aside from the material and human cost, caused a significant increase in tension between the local, innocent Irish immigrants and their neighbours.

A number of the group involved in the explosion were later executed for their role in the plot, including the ringleader, Michael Barrett[16].

Inmates You May Know

- Richard Burke – A member of the Fenian society (an organisation dedicated to the establishment of an Independent Ireland). He was sent to purchase weaponry in Birmingham for the society but was arrested and sent to Clerkenwell to await trial. It was Burke who was one of the targets of the failed Clerkenwell Outrage in December 1867[17].

- Joseph Scott – An inmate who died of tuberculosis, supposedly hastened by being forced to undertake hard labour whilst unwell in 1860[18].

Written by Danielle Yates

[1] Ward & Lock, The Visitor’s Guide to Places Worth Seeing in London: A Handbook to The Great Metropolis, (London, 1862), p. 55

[2] “London Metropolitan Archives Collection Catalogue” Search.LMA.Gov.Uk, 2021, https://search.lm.gov.uk/scripts/mwimain.dll/144/RESEARCH_GUIDES/web_deta…SESSIONSEARCH#coll13, [Accessed on 5th April 2021]

[3] “The Separate And Silent Systems – Attitudes To Punishment – WJEC – GCSE History Revision – WJEC – BBC Bitesize”, BBC Bitesize, 2021 <https://www.bbc.co.uk/bitesize/guides/z8bd3k7/revision/7> [Accessed 5 April 2021].

[4] “Clerkenwell Close Area: Middlesex House Of Detention Site, And Other Buildings | British History Online”, British-History.Ac.Uk, 2021 <https://www.british-history.ac.uk/survey-london/vol46/pp54-71> [Accessed 5 April 2021].

[5] O’Cathaoir, Brendan, ‘An Irishman’s Diary,’ The Irish Times, (1997)

[6] “History”, The Old Session House, 2021 <https://theoldsessionshouse.com/history/> [Accessed 5 April 2021].

[7] “Clerkenwell Close Area: Middlesex House Of Detention Site, And Other Buildings | British History Online”, British-History.Ac.Uk, 2021 <https://www.british-history.ac.uk/survey-london/vol46/pp54-71> [Accessed 5 April 2021].

[8] Ibid.

[9] Jessel, “Clerkenwell House Of Detention – History And Hauntings”, The Haunted Palace, 2021 <https://hauntedpalaceblog.wordpress.com/2013/03/08/clerkenwell-house-of-detention/> [Accessed 5 April 2021].

[10] “Clerkenwell Close Area: Middlesex House Of Detention Site, And Other Buildings | British History Online”, British-History.Ac.Uk, 2021 <https://www.british-history.ac.uk/survey-london/vol46/pp54-71> [Accessed 5 April 2021].

[11] O’Cathaoir, Brendan, ‘An Irishman’s Diary,’ The Irish Times, (1997)

[12] “Clerkenwell Close Area: Middlesex House Of Detention Site, And Other Buildings | British History Online”, British-History.Ac.Uk, 2021 <https://www.british-history.ac.uk/survey-london/vol46/pp54-71> [Accessed 5 April 2021].

[13] Ibid.

[14] Ibid.

[15] O’Cathaoir, Brendan, ‘An Irishman’s Diary,’ The Irish Times, (1997)

[16] Jessel, “Clerkenwell House Of Detention – History And Hauntings”, The Haunted Palace, 2021 <https://hauntedpalaceblog.wordpress.com/2013/03/08/clerkenwell-house-of-detention/> [Accessed 5 April 2021].

[17] Ibid.

[18] London Evening Standard, 1860. Death of a prisoner in the Clerkenwell House of Correction. [online] p.5. Available at: <https://www.britishnewspaperarchive.co.uk/viewer/bl/0000183/18600911/036/0005> [Accessed 12 April 2021].