Introduction

Great Yarmouth House of Correction, also known as Yarmouth Town Gaol or Yarmouth Gaol, is located on Tollhouse Street in Great Yarmouth. The road itself used to be known as Gaol street, but after the closure of the two prisons situated there the street was renamed.

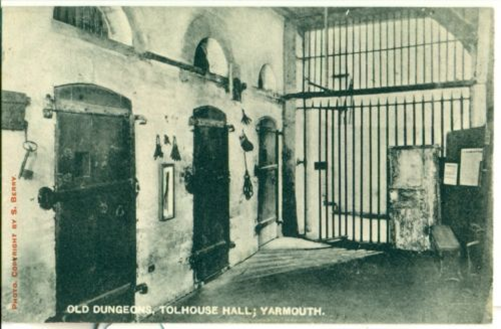

The borough gaol was originally a tollhouse, used by merchants in from around 1150 for the sale of fish and imported goods. It had many uses in the next centuries, from townhall to courthouse, but remained partially as a prison with inmates held in the basement until 1878 when the inmates were moved to Norwich Prison.

Background and history of the prison

The Tollhouse at Great Yarmouth is considered one of the oldest buildings in England. Whilst originally used for the sale of Herring and meetings of the burgess, freemen of the borough, King Henry III gave permission on 28th September 1261 for it be used as a prison[1].

“And forasmuch as where magistrates be, and offenders are to be punished, it is very meet there should be places appointed wherein the bodies of such should be safely kept and detained from liberty,[2]”

The upper floors were used primarily for public functions, courts and meetings, with the cellars being reserved as dungeons for the reception of prisoners. Initially only a borough court was held at the tollhouse, dealing with civil crimes and breaches of contract. By 1559, Queen Elizabeth I established an Admiralty court which increased the remit of the court to include naval crimes: these powers would remain in effect until 1823.

From 1491, an ordinance to hire a gaoler at a cost of 20 shillings, and a gown, from public rates was announced, but several further ordinances over the succeeding years showed ongoing issues with employees. In one instance there was a sacking for allowing a prisoner to escape and another ruling, that the gaoler could not “arrest any person without the special command of the bailiffs”. These examples highlight the potential ways gaolers could abuse their powers and even then, only in ways that were caught.

One of the biggest powers of the gaoler was a financial one, the expectation that prisoners would pay the gaoler for their bed and board. This allowed a crafty gaoler to make significant money on the side of his state offered stipend, that is until the law changed. In response to the first of these laws to curtail incomes received from inmates housed in a gaol the Yarmouth council voted a wage of £20 per annum from 1671 which had increased to £40 by 1808[3].

The Prison was repaired multiple times, but due to the structural limitations of its original foundations, many improvements could not be made and it was considered incredibly unhealthy and disorganised. In the 1808 Account of Prisons, the sick room had no fireplace, there was no chaplain or employment for any inmates and all of the different types and genders of prisoners were ble to intermix freely[4]. A suggestion was made in this account to purchase the adjoining property to consolidate into a bridewell and allow for more separation, which was the expectation across the country. This eventually took place although the space purchased no longer exists.

By 1870 the tollhouse was considered for demolition[5] as the building was cramped and could not provide the same standards of living as other, newer prisons. However, historians and archaeologists across the country raised the hue and cry, fighting against the local councillors plan for demolition, citing significant historical interest[6].

In 1878 it officially closed as a working prison and in 1883 became a museum. It has retained its museum status through both world wars and even partial destruction from bombing.

Inmates of interest

Pirates

In 1613, Thomas Jenkins, Michael Mugge, Edward Carter, Michael Smith and John Jacob, a combination of mariners and merchants in London plotted and boarded a Flemish ship in the Thames[7]. They overpowered the crew and fled with the ship and its goods but after docking in Yarmouth, the five were apprehended and charged with piracy.

This was the first trial for Piracy held in the Tollhouse, on the 26th of March 1613: the men were all found guilty. The justices, in an attempt to temper justice with mercy, only executed 3 of the 5, releasing Michael Smith and John Jacob. Pardoned by the King for their parts in the crime, they returned to society as free men.

Witches

Great Yarmouth was the seat of one of the most famous witch trials in England in what would later be known as, The Norfolk Witch Trials. In 1645 Matthew Hopkins, the self-proclaimed Witch-finder General, was invited to Yarmouth to uncover those who practised dark arts at the devil’s side[8]. He did his job well, and thoroughly, and on the 10th of September 1645, eleven individuals stood before the dock awaiting sentence for various magical crimes. Five were acquitted, one of whom would be tried again a year and a half later, but by far the most intriguing was that of Elizabeth Bradwell[9].

Elizabeth Bradwell

Bradwell was a poor, elderly woman who lived on charity and what she could scavage from the shore. Her neighbours would occasionally give her sustenance, but this undoubtedly bred resentment in the end. The townsfolk would eventually accuse her of harbouring spirits and turning them loose on those who would not offer her charity.

In 1644 she begged at the house of a man of good standing, asking if he might provide her with employment. His servant declined and soon after, the alderman’s son began to sicken[10].

Hopkins ordered the woman “watched” and whilst that word could mean nothing more sinister than observation it often included days of sleep deprivation with the watchers forcing the suspect to wake anytime sleep overcame them. Bradwell, after a short while, confessed to having a familiar in the form of a raven, of sticking an iron nail into a waxen image of the alderman’s son and of signing the devil’s black book.

She confessed again in front of the court at Great Yarmouth Tollhouse and was sentenced to hang with 5 other women, for her despicable crimes. On the 13th September 1645, Elizabeth was executed by hanging

The Prison today

The prison stands, having been lovingly restored after bombing, as one of the finest historical municipal buildings in the country. It runs museum events throughout the year, hosts after dark ghost hunting events and is open to the public.

[1] Clarke, W. and Heaton, A., 1921. Norfolk & Suffolk : painted by A. Heaton Cooper. London: A & C Black, p.171.

[2] Manship, H. and Palmer, C., 1854. The history of Great Yarmouth. Great Yarmouth: L.A. Meall.

[3] Neild, J., 1808. [An Account of the Rise, Progress, and Present State, of the Society for the discharge and relief of persons imprisoned for small debts throughout England and Wales, etc. By James Neild.]. L.P. London.

[4] Ibid 3

[5] The British Architect, 1875. The Tollhouse. Vol 3, p.27.

[6] ibid

[7] Archives.norfolk.gov.uk. 2021. Crimes and trials in Great Yarmouth – Archives. [online] Available at: <https://www.archives.norfolk.gov.uk/help-with-your-research/crime-and-punishment/crimes-and-trials-in-great-yarmouth> [Accessed 1 September 2021].

[8] Norfolk Record Office. 2014. Norfolk Witchcraft Trials. [online] Available at: <https://norfolkrecordofficeblog.org/2014/10/20/norfolk-witchcraft-trials/> [Accessed 13 July 2021].

[9] Norfolk Record Office. 2019. Elizabeth Bradwell: Accused of Witchcraft and Executed in Great Yarmouth, 1645.. [online] Available at: <https://norfolkrecordofficeblog.org/2019/10/28/elizabeth-bradwell-accused-of-witchcraft-and-executed-in-great-yarmouth-1645/> [Accessed 13 July 2021].

[10] Gaskill, M., 2005. Witchfinders : a seventeenth-century English tragedy. Cambridge, Mass: Harvard University Press.