Introduction

Ashbourne, formerly Ashborne, House of Correction was active between 1784-1828 and was located on Back Lane, Ashbourne in the county of Derbyshire[1]. Its purpose was to house low level criminals, who committed petty thefts, were serving short sentences or had been convicted of vagrancy.

Background and history of the prison

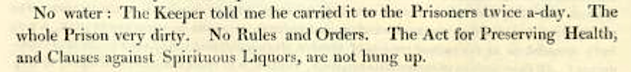

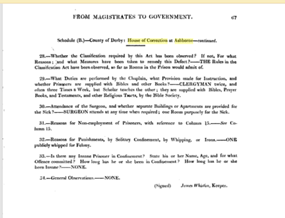

Prior to the 1800s there are very few records surrounding Ashbourne House of Correction, whilst reference is made to different Gaols in the area from as early as 1666 the black lane House of correction was not constructed until 1784. A report conducted in 1802 described the House of Correction as “very dirty” with “no rules and orders”[2] with the gaoler, living on the ground floor in relative comfort, with a fireplace and two glazed windows. In 1811, the House of Correction was inspected again. It was described as having two courtyards with a wall encircling the area reaching a maximum of 14-feet high[3], however this was not considered sufficient to prevent escape. The prison housed both male and female convicts, with the female inmates being incarcerated upstairs[4]. Overall conditions of the prison were poor with no bedding being provided upon arrival, the gaoler was expected to provide straw instead, and water had to brought up by the goaler as there was no source on site.

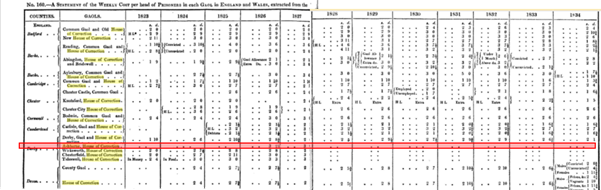

In 1835, the publically available records of revenue and commerce had an incomplete record of the weekly cost per head for each prisoner in Ashbourne House of Correction between the years 1823-1834. Earlier in 1826, it demonstrated the highest cost per head of any of the below listed counties and, were this cost were constant through the years, Ashbourne would have the highest average spend per head.

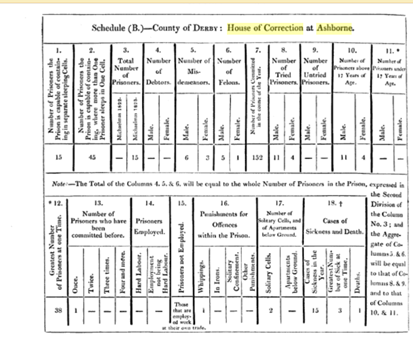

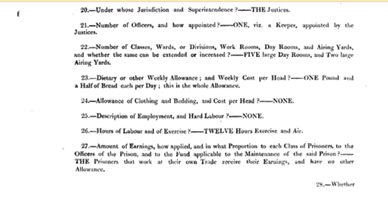

In the 1823 report[5], pertaining to the Michaelmas Quarter session, Ashbourne is listed as having a dedicated chaplain, unlike nearby houses of corrections at Wirksworth, Chesterfield and Tideswell. This chaplain visited two to three times a week alongside a scholar who provided rudimentary education. The inmates, however, were only provided with the barest essentials to survive; one and a half pounds of bread per day with no clothing or bedding allowance. Any inmate, if they wished to have an easier life, would have to work at a craft in their cell, with materials they purchased, and hoped to sell on.

Inmates of interest

John Ivy Wilson

John Ivy Wilson, sentenced to 14 years transportation for uttering false coin, sends a petition to the bank of England and begs for clemency. The gaoler of Ashbourne, who was responsible for holding the inmate. sensed an opportunity for enrichment and attached a letter to the petition and asked for ‘reimbursement of expenses for apprehending Wilson in the first place[7]. The bank responded ‘if he will send someone to them in London, they will provide three guineas for his trouble’[8]; the distance was a mere 148 plus miles away.

Sarah Holloway

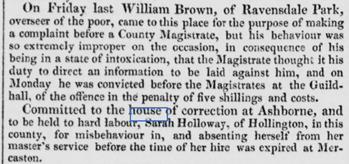

In 1824, a news paper documents the standard crimes that would land a person in Ashborne. Sarah Holloway, age unknown, was sentenced to hard labour at the House of Correction for an indeteriminate amount of time; her crime, absenting herself from her job before her contract ended[9].

Conclusion

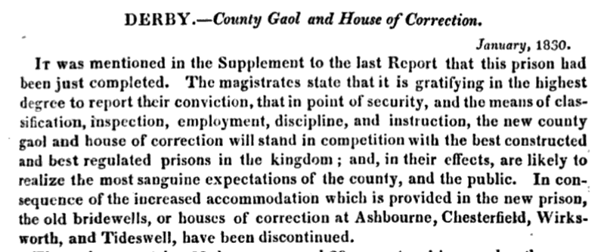

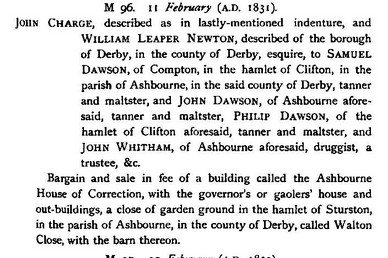

The prison was closed in 1828 after the New Gaol and House of Correction was built in Derby; the old prisons of Ashbourne, Tideswell, Wirksworth and Chesterfield were considered ‘defective’ and the greater capacity at Derby made it appealing[10].

As of today, the building where the prison once stood has been taken over by a ceramicist and illustrator who have transformed the interior into a modern, stylish home[11].

[1] “Ashborne House Of Correction – 19Th Century Prison History”, 19Th Century Prison History, 2021 <https://www.prisonhistory.org/prison/ashborne-house-of-correction/> [Accessed 10 August 2021]

[2] Ibid.

[3] “State Of The Prisons In England, Scotland, And Wales: Extending To Various Places Therein Assigned, Not For The Debtor Only, But For Felons Also, And Other Less Criminal Offenders. Together With Some Useful Documents, Observations, And Remarks, Adapted To Explain And Improve The Condition Of Prisoners In General: Neild, James, 1744-1814: Free Download, Borrow, And Streaming : Internet Archive”, Internet Archive, 2021 <https://archive.org/details/stateofprisonsin00neil/page/14/mode/2up> [Accessed 10 August 2021]

[4] Ibid.

[5] Google Books. 1824. House of Lords – The Sessional Papers Vol 168. [online] Available at: <https://www.google.co.uk/books/edition/Accounts_and_Papers/g7JbAAAAQAAJ?hl=en&gbpv=1&dq=%22ashborne%22+%22house+of+correction%22&pg=RA3-PA59&printsec=frontcover> [Accessed 28 October 2021].

[6] Ibid.

[7] ‘Letters, nos 201-300’, in Prisoners’ Letters to the Bank of England, 1781-1827, ed. Deirdre Palk (London, 2007), pp. 65-92. British History Online http://www.british-history.ac.uk/london-record-soc/vol42/pp65-92 [accessed 28 October 2021].

[8] Ibid.

[9] Britishnewspaperarchive.co.uk. 1824. Derby Mercury. [online] Available at: <https://www.britishnewspaperarchive.co.uk/viewer/bl/0000052/18240317/006/0003> [Accessed 28 October 2021].

[10] Google Books. 1832. Eighth Report of the Committee of the Society for Prison Discipline. [online] Available at: <https://www.google.co.uk/books/edition/Report_of_the_Committee/4P8SAAAAIAAJ?hl=en&gbpv=1&dq=%22ashbourne%22+%22house+of+correction%22&pg=RA1-PA7&printsec=frontcover> [Accessed 28 October 2021].

[11] Leevers, Jo, “Interiors: The Former Jail That’s Now a Family Home”, The Guardian, 2015 <https://www.theguardian.com/lifeandstyle/2015/oct/02/homes-cottage-industry-northern-england> [Accessed 10 August 2021]