So, tell us a little about yourself, your background and how did you get into this?

When I did my history degree many eons ago, I had to come up with a topic for my dissertation that had a good coverage of archive material. I was already familiar with archives as I started researching my family tree when I was 16. My local archive has an extensive collection of Dudley Poor Law Union records, which incidentally were saved from a skip by the archivist! I decided my dissertation should be about life in Dudley Union Workhouse, and this was my first attempt to write about the social history of an institution, the inmates within it and the staff who ran it. Years later, it became the starting point for my book Life in the Victorian and Edwardian Workhouse. Having discovered that there was a huge amount of archive material associated with prisons, I then wrote Prison Life in Victorian England. This was followed by Life in the Victorian Hospital. In all these books, I tried to find the untold stories of the people accommodated in these institutions.

Could you surmise what your newest book is about?

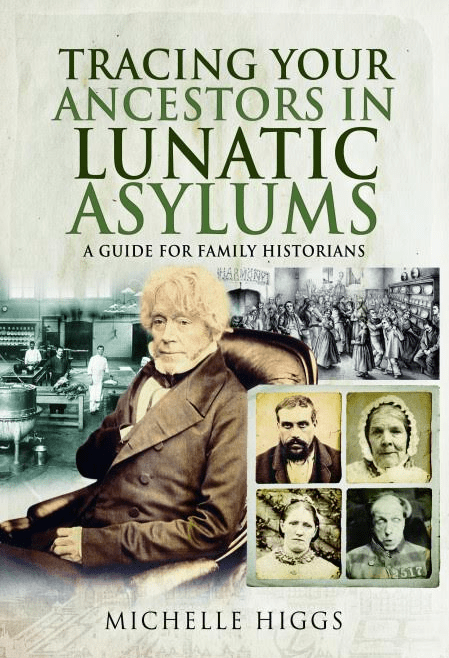

My latest book is another addition to Pen & Sword’s ‘Tracing Your Ancestors’ series (I’ve written two others). This one is called Tracing Your Ancestors in Lunatic Asylums and while it’s aimed at readers who are researching their family tree, roughly two-thirds of the book is about the social history of asylums in Britain, interspersed with real life case studies.

What are the barriers you faced when researching this book and how did you overcome them?

The main barriers were to do with getting permission from archives to quote from the records of eighteen different patients, who formed the basis for the case studies. With some archives, it was straightforward; with others, I was referred to the individual NHS Trust which owns the records and it was often difficult and frustrating to track down the person who could actually grant permission.

What did you feel as you wrote this book?

It was difficult to write and research this book as I was reading so many heart-breaking stories about people who were admitted to asylums and never recovered from their mental illness. I found it particularly distressing to read of young people in their late teens or early twenties whose futures were effectively stolen because they had to be hospitalised for the rest of their lives.

Do you think there any instances where asylums ‘worked’?

Yes, absolutely. The first county lunatic asylums of the mid-nineteenth century aimed to cure insane patients, not simply to incarcerate them. Recovery was possible in acute cases because time away from the stresses of daily life with fresh air, work therapy and nutritious food could significantly improve mental wellbeing. A rapid rise in patient numbers from the 1860s and 1870s meant that it was no longer possible to provide the same level of treatment. By 1900, lunatic asylums were places where chronic, incurable patients were confined with little chance of recovery.

Were there any differences in treatment between men and women, young or old?

No, the treatment was the same.

What are your top tips for researching ancestors?

Start with living relatives because oral history is a very important but undervalued source. But take family stories with a pinch of salt until you can prove or disprove them from the records. Don’t simply copy information from distant relatives’ family trees on genealogy websites; instead, always go back to the original source where possible.

Were any of your ancestors confined to asylums or prisons?

Luckily, none of them were admitted to an asylum, nor have I found anyone who was in prison. I wish I did have a ‘black sheep’ in the family because prison records are amazingly detailed!

How important is it that we, in a modern world, research our ancestors?

Researching our ancestors helps us to understand where we came from; it’s also really important that we learn from history. Sometimes we can feel detached from our Victorian forebears because they lived so long ago. But the problems they experienced were similar to our own, for instance, their mental health was just as fragile as ours. Family bereavement, the breakdown of a marriage or relationship, financial worries and stress caused by overwork are all universal issues, any of which could spiral out of control, leading to debilitating mental illness.

Lastly, where can people find out more about you or buy your book?

Tracing Your Ancestors in Lunatic Asylums is available from Pen & Sword (https://www.pen-and-sword.co.uk/Tracing-Your-Ancestors-in-Lunatic-Asylums-Paperback/p/16717) and Amazon (https://www.amazon.co.uk/Tracing-Your-Ancestors-Lunatic-Asylums/dp/1526744856/ref=sr_1_3?keywords=michelle+higgs&qid=1574105939&sr=8-3). Signed copies are also available from my website where you can find out more about me and my writing (www.michellehiggs.co.uk).

User Submitted Questions From Reddit

ZuleikaD

1. What records typically existed?

2. Were those records saved after someone was discharged or died?

3. Where were they archived?

4. Who is entitled to request copies of those records?

5. Where and how should someone request copies?

How do records and processes vary by era? How do they vary by country (UK, Ireland, US, Canada, Europe, etc.)?

How can people learn about the reasons their ancestors might have been committed? (Mental health problems, but also people with developmental disabilities, women who had sex and children outside of marriage, etc.)

How did class/economics affect who was committed, why, etc.?

I can only answer the parts of these questions which relate to the UK as my research and book is about British lunatic asylums. There’s usually a good coverage of records for county lunatic asylums (for paupers). You can find out which archive holds records for the asylum you’re interested in by looking at the Hospital Records Database (http://www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/hospitalrecords/). It’s no longer updated but it’s still a good starting point. Typically, records will include admission and discharge registers, case files, and death registers. Anyone can view these documents that are over 100 years old (many are also online via genealogy websites and the Wellcome Trust). For records less than 100 years old, the archive may grant permission to view entries relating to an individual if you can prove a relationship to him/her. The records themselves explain why patients were admitted to lunatic asylums.

MidcenturyGuy

1. What judicial and/or medical process was used to commit people to an asylum?

2. What were the significant changes to that process and when did they occur?

3. Where were the deceased typically buried?

4. Were graves marked?

5. Was there an effort made to return the deceased to family?

6. Were alcoholics and criminals committed based solely on those reasons?

In Britain, after 1774, a person had to be medically certified before being admitted to an asylum, although this did not apply to paupers. From 1832, an order for admission by a magistrate was needed for pauper patients; this became known as a ‘reception order’. After 1890, for both pauper and private patients, the signatures of two doctors were required on a medical certificate, as well as a reception order from a magistrate. Voluntary patients could be admitted without a reception order because they were not certified as being insane.

After 1930, people could be seen in outpatient departments in the early stages of their mental illness; they could then receive treatment without needing to be certified and compulsorily admitted to an asylum. If further treatment was required in a mental hospital, there were now three categories of patient based on ability to provide consent: voluntary, temporary and certified.

Voluntary patients could be admitted to a mental institution, regardless of their financial status, if they were able to make an application in writing to the medical superintendent. They could leave after giving 72 hours’ written notice, or within a 28-day period. Temporary patients were those who could not provide consent for their treatment in a mental hospital. To be admitted, a written application had to be submitted by a husband, wife or other relative, along with the medical recommendation of two medical professionals. Treatment was limited to six months in the first instance but this could be extended to a year; if treatment was still required after that time, the patient became certified.

When a patient was dangerously ill and death was thought to be imminent, their relatives were informed by letter. This was followed by a death notice after the patient’s demise. Relatives were given the opportunity to collect their loved one’s body; if not collected, there would have been a burial in the asylum grounds, usually in an unmarked grave.

A criminal would usually only be admitted to a lunatic asylum if he or she had been acquitted of a criminal offence on grounds of insanity. Those who were persistently drunk and disorderly would normally have been sent to prison or to a state-funded inebriates reformatory (if they had been convicted of drunkenness four times in a year); if, however, the prison medical officer diagnosed an underlying mental illness, they could be sent to a lunatic asylum for treatment.

Mayzowl

I have a somewhat-distant cousin, Lucy Mills, who married a man named Leon Swackhammer in 1925. In 1929, there was an article published that she tripped while making coffee and received first-degree burns and a head injury. 6 years later (at most), she was an inmate at the “Albion State Training School for Female Mentally Defective Delinquents” in New York. She died there in 1951, and was buried in an unmarked grave on the institution’s property.

My question is: How common was this in the 1930’s? How easy was it for a husband to condemn his spouse to an institution like this, in that era? I’m only seeing one side of the story, obviously, but to throw away your wife for 15+ years in an insane asylum… it’s unimaginable.

My other question is: Is there any way to access the medical records (asylum records) for this deceased cousin? Or is it all covered until confidentiality/HIPAA/etc now?

Unfortunately, I can’t answer this question as my research and book only covers British lunatic asylums – sorry!

The_latest_greatest

If the asylum is still existent, is it possible to find out what the diagnosis was for relatives from 80 years ago?

For British lunatic asylums, if patient records still exist, they will provide details about diagnosis and treatment. You can find out where records are held by looking at the Hospital Records Database (http://www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/hospitalrecords/). It’s no longer updated but it’s still a good starting point. Patient records contain sensitive clinical information so they are usually closed for 100 years. However, if you can prove a relationship to the patient, it may be possible for the archive to copy the information from the case files for you for a fee.