Abingdon Gaol has had quite the colourful past.

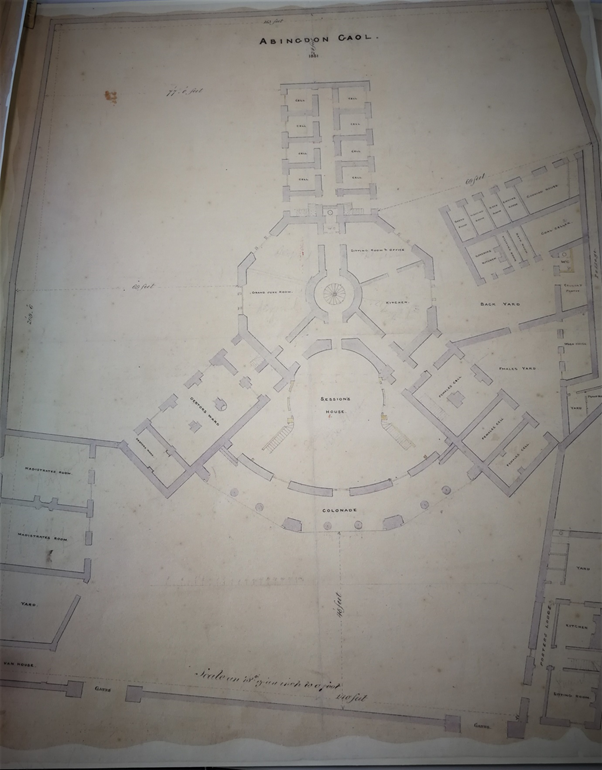

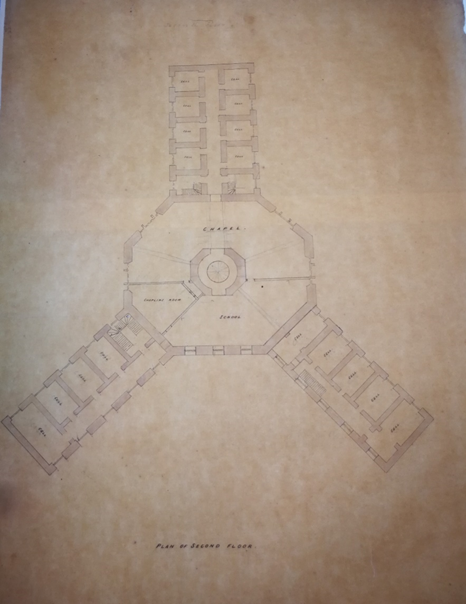

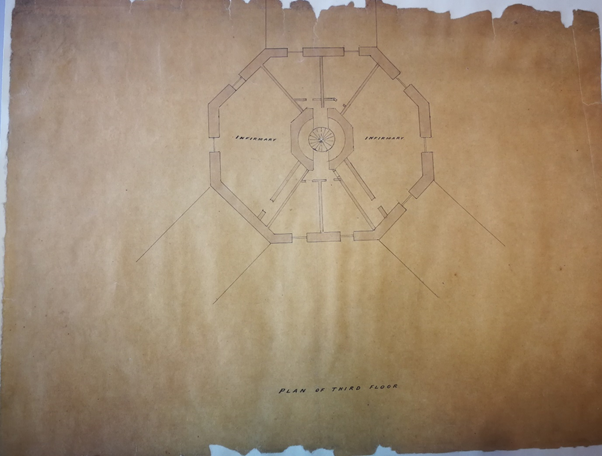

Built in 1811, Abingdon Gaol (more commonly known as the Old Gaol) was comprised of prisoners from the previous Abbey gateway Gaol and Thames St. Bridewell that had occupied the area before[1]. This new Gaol was expected to supersede the previous two, boasting three floors of cells, a chapel for prayer, a school intended to reform convict behaviour and an extensive infirmary to heal those who were injured or became ill during their sentence. However, the build of the new Gaol seemed doomed from the start, with spats over the costs of the build casting a long shadow.

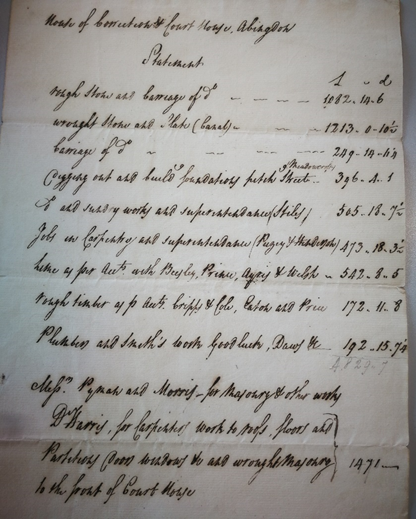

George D’Arville, of Oxford Timber Merchants, and Daniel Harris of Oxford builders, teamed up in the construction of Abingdon Gaol in 1805[2]. Harris was also attributed to the early architectural drawings of Abingdon Gaol, as well as holding the position of Governor of Oxford Gaol. By 1810, after the build was completed, D’Arville had written a letter claiming to have paid for all the costs of labourers and building materials to the Gaol, equating to £2,390. Of course, Harris disputed this and had provided an itemised bill of costs to each. In the end, D’Arville’s claims were deemed unfounded and neither men could be awarded the exact costs that they claimed for as there wasn’t sufficient proof.

The inmates were moved into the new building in 1811, situated at the back of the also newly built Courthouse, which had separate wards for male and female convicts[3]. According to a report, submitted in 1855 by Alfred King Judd the Governor of Abingdon Gaol, the prison had five wards: three for Female Convicts, two for Males. There were four ‘airing yards’, three for males and one for females. This was where inmates would take part in their mandatory daily hour of exercise. The report also details four work rooms, simply labelled “tread wheel, water wheel, wash house and laundry.” This would be where the convicts would complete six hours of labour in the summer, four hours of labour in the winter with one hour of exercise a day all year round. The weekly costs per head of keeping the inmates were detailed at around 4 shillings; with the costs of bedding and clothing costing £1 per annum for each prisoner. Those imprisoned would have to abide by the rules, no talking, swearing, damaging county property, non-refusal of ‘duty’, acts of violence or threats. Breach of rules would result in corporal punishment.

By 1844, a new Gaol had been built in Reading, larger in capacity and stature. This would become the rival to Abingdon, setting off a chain of arguments between the two as they fought for the position of the principle assize town in the County.

According to the ‘Visiting Justices book of reports 1860’, Abingdon in 1844 housed 875 prisoners to Reading’s 336[4]. By 1867, Reading held 909 prisoners in its cells compared to Abingdon’s small population of 199. Reports would suggest that Reading seemed to be the favoured prison in the County; deemed to be both fit for purpose and cost effective. With the allocation of more prisoners at Reading, costs per head were kept to a minimum, which conversely meant that Abingdon was haemorrhaging funds, supposedly due to their low prisoner count. The Abingdon Corporation fought hard to keep the prison open; the sessions and assizes held in the Old Gaol were said to be generating revenue for the town. They even went as far as to draw up an agreement with Reading that criminals should be tried and jailed in the respective boroughs in which they lived, to fairly distribute convicts between the two prisons. Even with the efforts made to keep the Gaol inhabited, many lobbied for its closure with backing from the County Magistrates of Berkshire.

By 1857, William Merry became the face of the unwavering argument for the abolition of Abingdon. He was outspoken about how the Gaol was costing the borough revenue, even going as far as making outlandish claims of money saved if the Gaol ceased to exist and frequently appealed to the Corporation to sell off the Gaol to recoup the losses incurred. Abingdon’s MP, John Thomas Norris, had written a pamphlet in response to Merry’s argument, bringing to light Merry’s lack of integrity and the twisted truth that was spun to gain favour for his cause.

An excerpt from his 1859 Pamphlet (pg8) states[5]:

“In a report submitted to the court last sessions, signed William Merry, and purporting to be a report of the Abingdon Gaol committee…it was stated that a saving of £600 (out of a gross expenditure of £554 per annum) would be effected by shutting up Abingdon Gaol…this the same William Merry, some ten weeks later, admits that the saving on average of the ten years last past would have been only £231 per annum: where, then, is the apology for having stated it at £600?”

He then goes on to say that during the midsummer sessions in 1856, Merry claimed savings of £200 per annum. Then in the Michaelmas sessions of the same year, claimed savings of £210 per annum. Three months later at the Epiphany sessions in 1857, Merry claimed a further potential saving of £400-£500 per year if Abingdon ceased to run. These claims, until Norris’s release of his counter argument, continued to inflate and dip at Merry’s will, with a final claim of £231 per annum detailed in Merry’s 1859 pamphlet.

Norris also makes a statement in his pamphlet on the legality of selling off Abingdon Gaol, stating: “…the Corporation thus prepared to sell and surrender that which they did not possess; and the county Justices, in accepting the offer, agreed to buy of the borough that which already belonged to them…”. This brought to the forefront the undeniable fact that no one really knew who the Gaol belonged to! Merry’s claims, the confusion over ownership and keeping in line with legislature were only a few of a host of factors that ended up delaying the prison closure by another ten years.

Eventually, in 1867, the agreement was finally made to abolish Abingdon Gaol, the reason for simply stated in official documents as ‘unnecessary’[6]. In 1868, the prison had officially closed its doors and moved its inmates to Reading Gaol, which in turn, meant that all business of the Court of Quarter sessions and assizes in Abingdon would be awarded to Reading Gaol. The cost of the litigation came to the sum of £207 11s 10d, marking the end of the struggle against the abolition of the Old Gaol.

What once was a House of Corrections built with such promise soon became a derelict structure[7]. Over the many years it has served as a grain store, slum housing and a leisure centre. As of today, the interior has been converted into luxury flats to let, though the outside structure still holds in its very fabric the history of what was once the ‘Old Gaol’.

Written by Karen Swaley

[1] Herald Series. 2020. Heralding The Past: The Long Arm Of The Law – From Abingdon To Rio. [online] Available at: <https://www.heraldseries.co.uk/news/16346612.heralding-past-long-arm-law—abingdon-rio/> [Accessed 9 November 2020].

[2] 1795. Correspondence, Committee Papers Etc Regarding The Building Of A New Court House And Bridewell At Abingdon, 1795-1818. [Letter] Berkshire Records Office, Q/AG2/5. Reading.

[3] judd, a., 1855. Abingdon Prisoners Report. [report] Berkshire Records Office, Q/AG/2/2. reading.

[4] 1860. Visiting Justices Book Of Reports. [Report Book] Berkshire Records Office, D/EX1847/1. Reading.

[5] Norris, J., 1859. Agreements, Correspondence, Legal Papers And Committee Papers Regarding The Abolition Of Abingdon Gaol, 1857-1868. [Letter] Berkshire Records Office, Q/AG2/4/1-3. Reading.

[6] 1868. Agreements, Correspondence, Legal Papers And Committee Papers Regarding The Abolition Of Abingdon Gaol, 1857-1868.. [Document] Berkshire Records Office, Q/AG2/4/1-3. Reading.

[7] Abingdon.gov.uk. 2020. Old Gaol | Abingdon-On-Thames. [online] Available at: <https://www.abingdon.gov.uk/history/buildings/old-gaol> [Accessed 9 November 2020].