Being arrested and then sentenced to penal servitude in Victorian Britain almost certainly guaranteed a miserable existence, in a miserable prison, surrounded by equally miserable people.

During the Victorian era there were several paradigm shifts in the way saw the people and world around them, from the advent and celebration of science and technology, as famously showcased during the Great Exhibition of 1851, to opinions on crime and punishment. The Victorians were right to be concerned about the rise in immoral or injurious behaviour, in 1840 there were around 40,000 offences per year, having rocketed up from 5,000 a year in 1800. Common punishments for crime included prison time in often inadequate and archaic institutions, transportation to faraway lands or the death penalty: a punishment which offered little opportunity for reform…

Capital Punishment

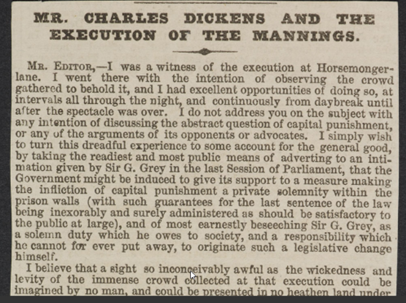

For convicts who committed capital offences punishable by death their futures were not very bright. To add to their grim prospects, if they were convicted before the Capital Punishment Act in 1868, their death could be a form of entertainment for the masses. Executions were public and Thomas Cook, famed travel agent, even ran trips for the public to go and watch: in 1849 alone, 30,000 people watched the execution of the Mannings a pair convicted of a murder of Patrick O’Connor later known as the Bermondsey Horror. Celebrated writer and reformist Charles Dickens, also watched the execution that day and wrote to The Times newspaper to condemn these public executions and suggested a more private way to deal with wrongdoers behind prison walls. Dickens suggestions were not taken up until 1868. This ended public hangings and required executions to be carried out in prisons, however it did allow the Sheriff of the county discretion around allowing newspaper journalists and relatives of the prisoner to be present.

Transportation

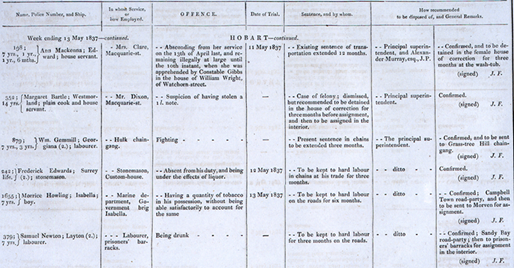

Transportation became an ever-increasingly important punishment within Victorian Britain as the list of capital offences was eventually reduced. By 1861 the number of offences punishable by death stood only at 2; meaning that the penal system had to accommodate for more prisoners. With little space, the colonies and Britain’s expansive empire came into play; Australia was a favourite destination to send prisoners and on average 460 convicts were sent there each year. Some unfortunate convicts were sentenced to transportation for minor crimes, as this extract from a prison register at Van Diemens Land, modern day Tasmania, shows. Frederick Edwards, a stonemason from Surrey, was sentenced to life for being ‘absent from his duty, and being under the effects of liquor’. This punishment seems awfully unfair for the crime committed…

Nor was Frederick alone in this as the extract shows a number with equally lengthy transportation sentences for seemingly minor crimes.

So, if a convict’s fate had been decided and the sentence didn’t mention ‘transportation’ or the dreaded ‘execution’, what else?

A stay in a Victorian Prison

The Victorians were worried about the rising crime rates across cities and rural areas, spurred on by the Industrial Revolution which saw cities expand and populations explode; which naturally brought with it an increase in criminal activity. The Victorians are credited with introducing what we see as the modern constabulary, with Home Secretary Sir Robert Peel introducing the Metropolitan Police Force for London and the surrounding districts in 1829 with the passing of the Metropolitan Police Act. Prior to this, England was policed by various watchmen, constables and other policing agents who were largely viewed as ineffective due to corruption and the receiving of rewards for successful prosecutions. Peel’s introduction of a uniformed police force in London, and later rolled out to all other Royal Boroughs and rural areas, saw a coherent Police Force who had to adhere to the same rules and procedures, as well as tasked with being a deterrent for criminal activity. However, this introduction of a more established and visible policing force did not satisfy the Victorian’s worry over the rise in crime and criminal activity, so a programme of mass construction and repair of prisons was rolled out. These large stone deterrents cropped up all over England and between 1842 and 1877 alone, 90 prisons were either updated or built. These prisons both old and new were not as instantly final as the death penalty, despite some inmates having been sentenced to Life in prison, but were to act as an unpleasant place to deter repeat offending and dissuade potential criminals.

Death in Prison was an all too real possibility for inmates; official figures for prisoner deaths for the 19th century are unknown, however smaller sample studies suggests that the numbers could be very high indeed. Prison death rates were higher than the general population, with diseases such as Typhus, which was known as ‘gaol fever’, having devastating effects. Prisons could be very unsanitary places where disease could easily spread if brought in from the outside via new prisoners or staff members. Poor sanitation combined with prisoner’s small rations and in many cases malnourishment, alongside overcrowding, was a recipe for disease to spread and take hold of susceptible inmates. It wasn’t just the prisoner’s diet that left them more susceptible to diseases, but also some of the Victorian ideas on how to keep prisoners busy whilst serving their time.

Common activities for prisoners included boring, tedious hard labour which could go on for hours each day, such as separating strands of rope known as picking oakum or walking the dreaded Treadwheel. The Prisoners would hold onto a bar and walk up the wheel causing it to turn, the point of this labour being to power machinery in the prison. Prisoners would walk the wheel for ten minutes and then have five minutes off, repetitively over a period of eight hours which was the equivalent of climbing around 8,000 feet. These forms of hard labour were to be done in silence, to occupy the body as the mind reflected on their behaviour and choices. Such was the importance was contemplation, that a punishment book from Coldbath Fields prison in London recorded over 11,000 offences against this rule in just one year. This tedious and physical hard labour would have taken its toll on the prisoners and their general health, with the small rations not providing them with enough energy to continually perform these tasks.

Coldbath Fields prison recorded the deaths of 376 prisoners from 1795 until 1829, in 1829 the mortality rate equalled 35.4 deaths per 1000 people per annum. Other prisons recorded similar figures and trends, with Newgate prison recording 816 inmate deaths between 1788 and 1837; 10% of this being inmates who were only awaiting their trial! Deaths amongst prisoners were subject to inquests by the local coroner, however these inquests were often vague or protecting the interests of the prison itself. Up until 1823, the juries for prison inquests were made up of 50% prisoners and 50% local residents. Records for inquests denote a general disinterest from coroners and juries with establishing the cause of the inmate’s death; commonly records stated ‘natural causes’ or a ‘visitation of God’ rather than a true diagnosis. The latter explanation was scarcely further investigated and could have been used as a cover to prevent any examination of prison practices or neglect. Dr William Farr, a statistician who compiled figures on the deaths in English prisons, complained in 1837 that “the inquest in gaols is at present very much a matter of form”.

To conclude, during the Victorian period prison would have not been a very sanitary or happy place to be, with prisoners subject to hard labour and improper conditions it is no wonder that the death rates were so high.

Written by Lydia Cauldwell-Ball