In August 1926 a gentleman died in Woking of, what was at first supposed to be, a cerebral haemorrhage and senility. Little was known of his life and no one (or at most 2 people depending on the source) attended his burial. Indeed, the grave itself, denuded of stone or inscription, moved strangers to such pity that they brought flowers to adorn the barren ground. Forgotten in life, unknown in death, thus might have ended this tale of emptiness and mystery. Then a guarded police investigation and newspapers sworn to secrecy: a will was found, witnesses interviewed and a body exhumed.

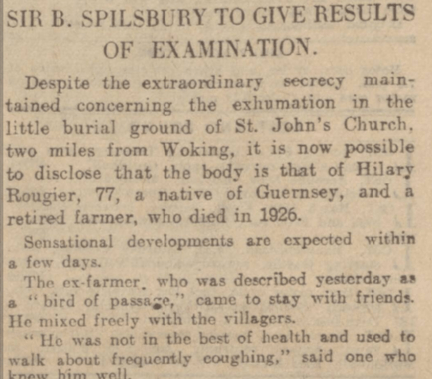

On the 15th March 1928, workers from the London necropolis company, erected 5-foot canvas sheets and dug down to the oak coffin below. Once raised to the surface, the nameplate was hastily removed. Such was the need for clandestine cover in this case, that a group of workers were sent to another part of the graveyard to dig a fake, vacant plot. The media circus began and at a conference, the Vicar of St. John’s in Knaphill made an announcement about the exhumation of a body, declining to name it due to ongoing research by police, deigning only to describe the male as a ‘bird of passage’. Sir Bernard Spilsbury, the home office pathologist, examined the body and surrounding soil before removing 3 jars of dirt and viscera for further investigation.

In the background, superintended Boshier and Deputy Chief Constable Kenward conducted interviews in Woking, followed leads in Horsham and all under the utmost confidentiality. The papers, despite being sworn to secrecy, having correctly guessed the man’s identity after looking at the burials register for St John’s, ran with the story anyway.

‘Identity Revealed’ ran the Sheffield Evening Post and a name, Hilary Rougier, ex-farmer aged 77 years old. Born in Guernsey on the 28th October 1848 to Hilary Rougier and Marie Ann Cary, a distinguished Guernsey family, Hilary Jnr. studied at Hayes Grammar School, Elizabeth College and later at Dinan in France for 18 months. He became a ‘farm pupil’ in Berkshire and Somerset for many years before setting up shop on his own, farming in Reading for 7 years. Then For 18 months he lived at a remote farm near Market Harborough in Leicestershire before he retired, moved back to Guernsey to enjoy ‘leisurely pursuits’ such as hunting and horse riding. Hilary returned to England, North Devon, in 1903. In July 1926, he arrived at Knaphill and stayed at the Nuthurst guesthouse with a family friend, a man called William Lerwill and his wife May St Leger Lerwill.

Throughout his time in Knaphill, Hilary became a notable figure. A local shopkeeper remembered him thus “Mr. Rougier used to go for a walk through the lanes every day until he became too ill…he was always accompanied by a spaniel. Walking with his head bent, he always seemed as if he wished to avoid talking to anybody, though occasionally he passed the time of day, but that was all. I think he suffered from asthma, for he had severe coughing fits.”

The plot thickened further with the discovery of a will, dated 28th October 1919, showing that he bequeathed “all property to my dearly beloved sister”. Hilary, it seemed, had once been an incredibly wealthy man with property all around the UK; however, a distant relative stated that by the time of his death his net worth was £79.

Then another startling turn. On the same day that the name of the deceased was officially revealed, the police sought to speak to the former nurse of the Lerwills, allegedly of French extraction. It was later disclosed that her name was Marjorie Helen Aldridge, a young-looking woman of 35 years of age who was slightly deaf. A manhunt began and she was found, eventually, in Scotland, where she had been holidaying and had, according to her, not read any newspapers nor heard of the ongoing investigation. She met with Superintendent Boshier in the Midlands and gave her evidence.

There was radio silence for a while as the police gathered evidence and awaited the results of the autopsy. The media, starved of attention, went into a frenzy. They dogged Boshier’s every move and each day had some piece of new information or evidence to report. There were intimations on potential suspects, where and what Boshier was taking to his ‘interviews’ and even an early leaked report on the autopsy results: negative for poison. As days grew into weeks finally, on the 17th May 1928, the police concluded their search and an inquiry begun.

Many were those who had been interviewed nationally and, due to the media frenzy surrounding the case, the inquiry began with a ‘small crowd’ gathered around the Woking Police Court. Mr. and Mrs. Lerwill arrived together and sat near their counsel J.E. Symes and in attendance, was also the counsel of Mrs Carey-Smith, sister of Hilary Rougier: Mr A. W. Crosso.

The Coroner addressed the jury and stated “You will hear medical evidence given by Dr. Brewer who attended the deceased in his last illness. You will also hear evidence from Sir Bernard Spillsbury, who conducted a post-mortem examination, and from Mr. Roche Lynch, with regard to the result of an analysis he made. In this case certain information came to my notice and I order the exhumation of the body. The man died in the month of August 1926, nearly two years ago, and was then buried. I decided to hold an inquest, and issued a burial order under which re-burial has taken place.”

The first witness to testify was Mary Reeves, a trained nurse, who was asked in early August 1926 to visit by the Vicar of St John, to visit Hilary as he was dying and needed “some attention”: when she arrived, he had already passed away. Under questioning, she admitted that she had prepared the body for burial and that there were no abnormal or unusual signs on the body, nor were the sheets stained.

The next witness to be called was Dr. Brewer who, on Mrs Lerwell’s request, had visited the patient prior to death and described him as being an ordinary healthy, old gentleman for his age but continued to say “I noticed he appeared to be very subdued”. When pushed further for an explanation, he stated “I noticed that he never spoke for himself, but Mrs. Lerwill monopolised the conversation, and seemed to speak on his behalf…he did not volunteer any statement or make any remarks on his own. Mrs. Lerwill made a remark to me that he was peculiar as to his feeding. He took his food by himself”. In addition, Brewer also recanted his initial cause of death ‘cerebral haemorrhage and senility’ owing to the pathologist’s later findings. James Fry, the undertaker, was also asked perfunctory questions about the burial, exhumation and reburial.

Sir Bernard Spilsbury was next to the stand and had a rather puzzling report to make; there were no signs of poisoning which would indicate murder or disease, which would suggest natural causes in the deceased’s body. However, that is not to say that there was no poisoning at all.

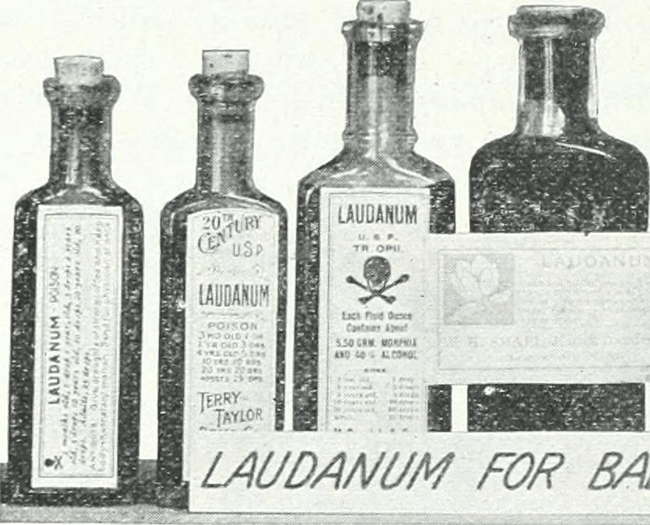

Dr. Roche Lynch, home office pathologist, took the stand and stated that alkaloid morphine was found in the organs he analysed. Indeed, that fact that morphine could still be traced some 18 months after death, given that it tended to ‘disappear as putrification proceeds’ suggested a ‘considerable quantity was taken – quite possibly a fatal dose’. Morphine took 6-12 hours to work and the symptoms witnessed by Dr. Baker were consistent with morphine overdose.

119 articles were taken from Nuthurst, amongst which were bottles of laudanum of the type which may have killed Hilary. The residence was formerly that of a doctor, rented to the Lerwills by his daughter Mary Beatrice Hope after his death, and the bottles were likely his. Mary recalled coming back from holiday in October 1928 to find the residence empty. She remembered that one of the bottles was possibly much fuller than its present state and one of the rooms of the house ‘smelt musty and not very pleasant’, also that a headboard had been polished and cleaned but a part had looked grey. Lillian M. Hope, sister of the above, stated also that the moment they got home they were told “Mr. Rougier had died” but not by the Lerwills. Indeed, the Lerwills had absconded and the promise to pay for rent in monthly instalments did not materialise after the first down payment.

Miss Alice Dayborn, a day domestic helper at Nuthurst, recounted that Hilary used to ‘potter around the garden’ most of the day. About three weeks into working at Nuthurst, Mrs Lerwill remarked that Hilary was ‘not looking very well’ and she sent for a doctor. Marjorie Helen Aldridge, the errant nurse now almost on the point of fainting, whilst at the stand attested to Rougier being a paying guest of the Lerwills and that he “had not his full voice, and seemed always to speak under his breathe…he was very feeble and not eating before his death”. Regarding relations between the Lerwills, she stated that they were both “affectionate” and “fond”.

Richard Hillier, nephew-in-law to the deceased, took the stand and what he had to say would change the course of this case. Richard was notified of his uncle in law’s demise on the same day that he died and whilst arranging funeral preparations, noticed that several his personal belongings were missing. All that was found in the vicinity of Hilary’s deathbed were a few newspaper cuttings and some coins; his chequebook was missing. The funeral arrangements also elicited strange behaviour from Mrs. Lerwill, when she suggested not only a speedy funeral, as it was hard on her children, but a cremation also.

Arthur Wilso Crosse, the solicitor involved in writing up Hilary’s 1919 will, paid a visit to Nuthurst upon hearing the news of his erstwhile client’s death and remembered that Mrs Lerwill “rather resented my appearance… [and] referred me to her solicitor at Brighton”. No wonder he was resented, as Crosse’s visit wasn’t just a perfunctory one and as he delved into Hilary’s affairs, discovered that of the 5,000 pounds of his estate that should’ve remained, only £79 was accounted for. When asked what the Lerwill’s solicitor had to say, he responded “he ought not to say…I did not obtain any satisfactory result”. A great many stubs for cheques made payable to the Lerwills by Hilary, of denominations between 40-2,000 pounds, was discovered.

At this point Hilary’s sister, Mrs Carey-Smith, took the stand and attested to Hilary’s inheriting a large sum from their father as well as his frugalness, reiterating that he was ‘careful with his money’. Mrs Carey-Smith last saw her brother alive in the Spring of 1925, when he sold a house in Guernsey to the tune of £3,080: Mrs Lerwill was also in attendance. The last time she heard from her brother was a fortnight before his death; he made no mention of any health or money problems and seemed quite himself.

The nurse, Helen, was questioned again and said that she was worried about Rougier on the night before his death, on account of his stumbling to bed, but he reassured her he was alright. When asked if he was depressed, he replied in the negative, likewise when questioned if ever he was suicidal or had harmed himself. When asked about bottles, she claimed she only seen those prescribed by Dr. Brewer, for Hilary’s throat, and nothing containing morphine. Helen also drew attention to the fact that one night ‘while playing cards, Mr. Rougier suddenly lost his memory’. Lastly, poison in his food was ruled out as Hilary’s last meal was fed to the dog after and the dog was still alive.

William Lerwill, currently unemployed, then was called to the stand.

In his testimony he stated that Rougier wrote to him, asking to stay with him confirming how the arrangement at Nuthurst came to be. Whilst living with them his (Rougier’s) cough got worse, becoming ‘very bad’, and that the Rougier said a ‘doctor was no good to him, as it was more a case of old age’. The coroner pushed further, asking for why the doctor wasn’t sent for sooner, William replied that Hilary had been getting worse for a while and that the doctor could do nothing. On the night Hilary died, William’s car had broken down on his way back to Woking from Colchester. When pressed as to whether he had anything else to say, William said there had been hearsay about ‘money matters’ and that to clear things up, answered that every cheque given to him was signed by Hilary and gifted from time to time to ‘help him’. These, William claimed, were gifts and done entirely of his own volition.

The coroner queried that, having no job, did he have a private income? William replied no, but that he had wanted to start up a business in Woking beforehand, but it subsequently failed. William added that Hilary paid no fixed rent amount whilst staying with him but did indeed give him money to pay off his debts. It later transpired that many of the cheques were written in William’s hand but signed by Hilary. When asked as to why, he stated that the deceased had said ‘Just write it out and I’ll sign it’.

Under further questioning, it was discovered that at some point Hilary had induced William to buy him some laudanum for his dog’s claws, but when asked where he had obtained it from, he could not say where. Curiously, a search of all chemists in Woking and Horsham, places Lerwill visited, discovered no chemist who had sold the bottle to him; all pharmacies by this time had to enter logs into their poison sale records, for laudanum and other dangerous substances.

Lerwill, now technically separated from his wife, when pressed on the strangeness of his taking all but £79 of Rougier’s money before he died, responded ‘No, there was nothing extraordinary in it’. The inquiry was adjourned and the coroner, in summing up, stated that several anonymous letters had been received by himself and by the jury and that these should be ignored.

As a crowd of ladies in summer dresses waited outside the court, Mrs Lerwill remained inside whilst in the courtyard, Mr. Lerwill smoked cigarettes as he ‘joked’ with his counsel.

The verdict came back ‘Morphine poisoning…not self-administered’. Judgement made, all inside were free to leave as no perpetrator could be pointed out. Mr. Lerwill on leaving, spoke sharply to Superintendent Boshier before exiting as a free man with his wife, the woman he had allegedly not spoken to throughout the trial.

It seemed that the mystery would remain just that, unknowable and unsolved. As the newspapers held their breathe, for weeks, then months, the public clamoured for more information until one day, news came: a new trial. But it was not the follow-up to the inquest, no, but an altogether different beast.

The Lerwills, suspected poisoning perpetrators, were taking the ‘News of the World’ to court for libel. It transpired, that the paper on 3rd June 1928 had run with the headline ‘ Who poisoned Hilary?’ beside a picture of the Lerwills. This had, allegedly, caused untold grief to them and that they had ‘mental anguish’ as a result of it. In addition, they had received hate mail and drawings of nooses. Rather than face trial, the paper gave them a ‘substantial sum’ and it was settled outside of court.

Over the years there were tantalising mentions of the case, from Boshier being recalled off holiday in September 1928 to do more work on the case, work which did not see the light of day, right up until his retirement in 1930. Further mentions in the 1930s refer to it as an ‘unsolved case’. There’s even a death of a ‘Charles Joseph Rougier’ in 1931, which the rumour mill tried to link to Hilary but with no luck. Indeed, the trail went utterly cold and it would seem no further information would come to light. Until a final startling twist in March 1934.

William Knight Lerwill, after the inquest, gallivanted around the UK and Canada frittering away the £5,000 sum given to him by the news of the world and another paper. In and out of work, setting up businesses which inevitably collapsed, Lerwill slipped back into his former state of penury: unemployed and homeless.

He visited his uncle in Kentisbury, Walter Lerwill, whom he hadn’t seen for 12 years. William’s visit rather than being one of sentimental purpose, was a pragmatic one: he needed money. His uncle, understandably taken aback, gave him ten shillings and some silver and William departed for Combe Martin in Devon. He stayed at the Deck of Cards hotel and registered under a false name, W. Knight, and brought no luggage. He spent five nights there, going out some evenings or else playing shove ha’penny in the saloon bar. During this time, he had asked the proprietor’s wife if he could borrow money, she demurred, and so he asked her son. The father, owner of the hotel, overheard and eventually agreed to lend him one pound.

Lerwill, claiming the previous name (knight) was a false one, gave him instead a new one which was equally fallacious. He claimed he was selling a property in Combe Martin and that he would pay him back from the sale of it; this too was a lie, a lie the proprietor suspected.

His final morning at the hotel, Lerwill saw a picture of a man being arrested in the newspaper and, according to the proprietor, became ‘terribly agitated ‘and left without settling his bill. The proprietor some days before had remarked on the strange behaviour of his guest and phoned up The Queen’s Head in Ilfracombe, a place Lerwill said he’d formerly stayed at, and they confirmed he had been there…but didn’t pay for his lodging.

Concerned, the proprietor spoke to PC Yelland and the officer agreed it was odd behaviour and agreed to speak to the suspect. That morning, Lerwill walked about town for some time before the officer, Yelland, spotted him. They walked and talked, despite Lerwill’s agitation, and then out of nowhere William said “I want to talk it over with you….where’s the nearest police station?”

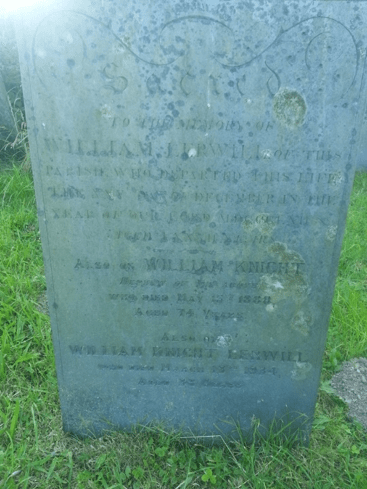

Yelland took him to the station but upon getting near, his charge changed his mind, walked ahead and behind a car, took out a small whisky flask and drank: he collapsed dead straightaway. He had consumed half an ounce of prussic acid (cyanide) enough to kill the man and many more besides. Questioned later, Yelland had no idea what the ‘it’ was that Lerwill wished to talk about and had not even mentioned the unpaid hotel fees in the course of their conversation. An inquest into his death found the cause, predictably, to be suicide and he was buried at the family tomb, in a private ceremony at Combe Martin.

The murder was never solved.

Whilst it is possible to infer from the evidence possible culprits, the mystery is all the stranger for there being no true resolution. Mr. Lerwill’s behaviour after Rougier’s death was incredibly strange and the nature of his suicide even more so. But he was not there on the night Hilary Rougier was murdered and so he can’t have given the fatal dose. Mrs Lerwill whilst present, did not benefit from Hilary’s murder at all and all the cheques went into her husband’s account, not hers; the pair also split shortly after. What motive, if any then, did the various doctors and nurses shuttling back and forth from the residence have for killing Hilary? None too it would seem.

We may never know who the true perpetrator was.