Last month The Institutional History Society took a tour around a local hidden gem: The Guildford Spike.

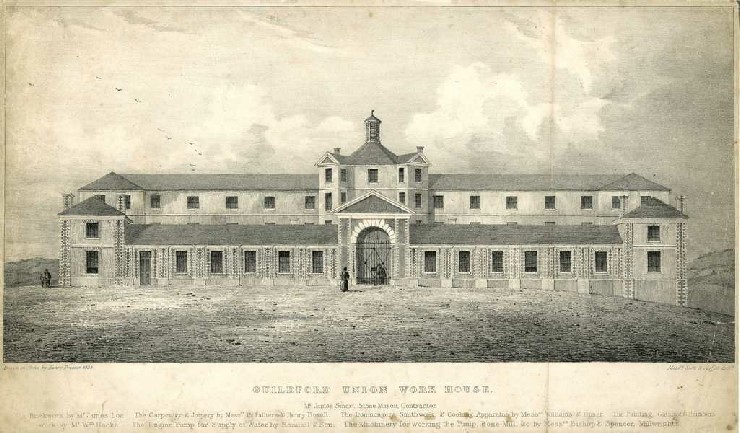

Hidden up a hill, close to the station, the Spike is what’s left of the casual ward for the Guildford Union Workhouse. The Workhouse was completed in 1838 as a response to the changes in the poor law. The Poor Law of 1834 legislated that no persons could receive poor relief or money from authorities except in a workhouse. The workhouse was heavily subscribed, in spite of the harsh conditions, and often very busy; until the 1870s when the able-bodied poor began to utilise the casual wards far more.

A casual ward provided the best of both worlds, that is to say for a little work, they got a little food and shelter. People who utilised workhouses and casual wards were referred to as inmates, perhaps as a deterrent to use. An inmate would be registered, bathed, fed, and work in the morning like the regular users of workhouses, but inmates would then be released to carry on their journey to another workhouse.

The casual ward at Guildford opened in 1906, and it continued housing wanderers right up until the 1960s!

With scant knowledge of this, we entered the courtyard and were treated to an exciting and interesting tour led by David Rose (a Guildford local, author and volunteer with the Spike). The tour began with a short video depicting the lives and admission processes for this transient population.

We learned some wonderful Victorian phrases and the meanings behind different types of Hobo graffiti (Good food here? Or is the master a keen on providing a beating?). We discovered the different types of contraband which could be smuggled in, and how a casual inmate may fake his name so he could return again within the month.

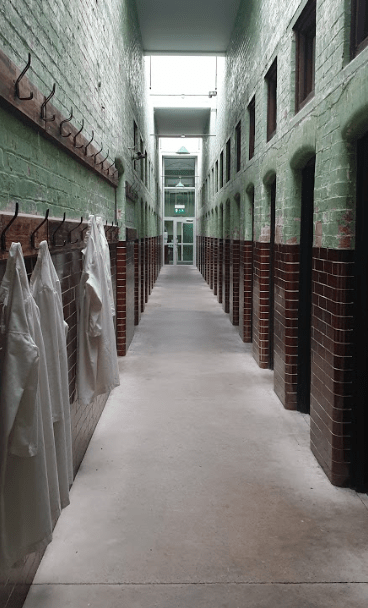

After this, it was time to walk through the building itself. Wandering through the main hall, inmate cells either side, we were thrown into the world of the poor. Despite the modern lighting and some improved heating, it was cold. The high ceilings and greenish walls lent the alley a clinical atmosphere. Everything here was made with the intention of discouraging the poor. Help, in the 19th century, was a cold handout, a frosty reception, to discourage lazy itinerants and malingerers. Spy holes were in each of the doors also, so warders could keep an eye on the inmates. Hard labour was also in plentiful supply; rock breaking was a frequent choice, followed by picking oakum using a “spike”, a sharp tool that lent its name to the ward.

The ward was cold, uncaring and echoing. There appeared to be little chance of a good night’s sleep and, for those interred there, no peaceful morning either as work would have to carried out before the cells were unlocked and a meal ticket provided.

Interestingly if an inmate paid for their lodgings, a nominal fee but still out of the budget for many, they weren’t expected to take part in manual labour and were allowed to leave the workhouse immediately in the morning. This had a knock-on effect of improving their chances of gaining a day’s work in the local area (all of the jobs being filled before the labouring vagrants were released). This ended up creating a two-class system. Those who could pay could earning more, and being able to pay again, whilst those who could not were forced to take the tramping paths between workhouses and hope for a lucky day’s work.

The Spike is one of only two casual wards left in England and contains unique architectural features that aren’t found anywhere else. It’s a rare and important reminder of our past and, even more so, a fantastic day out. So if you’re ever in the area, it’s well worth a visit: you never know what you might discover!