‘After committing the offence, the prisoner repaired to a public house, where he shortly afterwards was apprehended by a policeman, when he owned his crime, and said that he hoped his wife was dead. It came out in evidence that he had previously ill-used her and had threatened to kill her’[1]

Summary

Aaron Rungay was a hard man who lived a hard life. Born in or around 1802, he was a waterman by trade, a profession his father also pursued. For much of his life he and his family were never far from the workhouse, the privations of poverty or the police. Things went wrong early on. Aaron was no stranger to the law, committing his first crime of theft in 1823, then 1825 and again in 1836. Despite this, Mary Thompson married him on the 12th August 1845 and subsequently bore him several children, sadly losing their second baby after a matter of months. But rather than such trying circumstances bringing the family together, it tore them apart. On the 17th July 1853, Aaron Rungay attempted to murder his wife with a flick knife after suspecting she was having an affair with her brother-in-law. He gouged her hands and throat in an attempt to kill her but was thankfully stopped by their neighbours. For this crime and the brutality of its means, he was sentenced to life in prison. Aaron died at Woking Prison on the 31st July 1864 having served 11 years of his sentence and was buried in Guildford.

Early Life

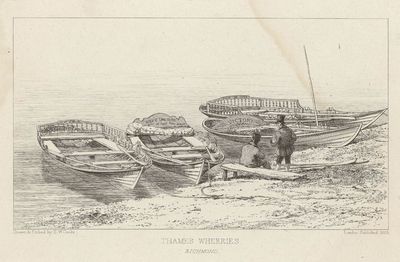

Little is known of Aaron’s early life, indeed, even his birthdate is mired in mystery and must be inferred from other sources. It is likely that Aaron joined his father Robert as a waterman at an early age. For hundreds of years, people would catch a boat from Gosport to Portsmouth, or to and from boats stationed in the harbour to the mainland, and whilst this was not a lucrative trade, it provided a relatively steady income. Life was hard upon the boats as, owing to the harbour’s natural geography, there was little wind and therefore the vessel would have to be rowed by hand[2]. Being a waterman also had its perks for those with a criminally entrepreneurial mind, like ready access to naval stores, an easy getaway and an alibi for being out on the waters at all hours. Aaron committed his first crime in 1823, the start of a career spanning almost 40 years.[MG(C1]

The Crimes Part 1

On the 16th February 1823, Aaron, Henry Adams and William Norley all of Gosport stole fishing netting from a place called Spithead. The property belonged to William Newman. For this he served 1-year hard labour, it being a first offence[3]. It wouldn’t be long before he committed his second crime. Just 3 years after having served his first sentence, Aaron was again in the docks, this time for having naval stores, property of the king, on his person: 41 fathoms of chord and 53ft of fir planks[4]. His co-defendant, Thomas Hawkins, spoke for five hours to the court but ‘failed to establish a single fact’ and the judge, noting they both had previous convictions for similar offences, decided to ‘check this species of depredation, by awarding the most severe punishment against such offenders’: transportation, 14 years. Aaron would go back to the seas, but this time as an inmate on The Captivity, held at his majesty’s pleasure.

The Captivity, a decommissioned relic from the Napoleonic wars, was moored at Devonport and throughout Aaron’s duration there as prisoner number 9, his behaviour was described as either being good or very good[5]. He (as Prisoner no. 7792) was latterly transferred to the Leviathan, moored at Portsmouth where he served the remainder of his sentence before being pardoned on the 10th November 1834 after serving 11 years[6].

Aaron was not there to witness his mother, Ann Rungay’s, burial on the 15th December 1832. She was interred in Gosport’s Parish Church at the behest of the workhouse where she had been working and staying[7]: the Rungays were no strangers to the ‘poor’ institutions of Victorian Britain.

Aftermath

Earning a livelihood as a waterman during this period was becoming increasingly hard, with the first floating bridge installed at Gosport in 1838. The bridge effectively stole much of their custom and a letter from the watermen to the Prime Minister requesting its termination had been largely ignored. Added to this the newly arrived railway in 1841 and it was the beginning of a perfect storm.

But, for a time at least, Aaron turned things around or, at the very least, was far better at hiding his crimes.

In the 1841 census Aaron is living at Stead’s Yard in Alverstoke, aged 40, and listed as a labourer living with his common law wife Mary Ann Dewey, a 33-year-old widow, and their son Henry aged 5[8]. Indeed, the two are not married until the 12th August 1845[9]. This was possibly instigated by the birth of their son George in October 1844 followed by his premature death 3 months later. Perhaps they had hoped to avert their God’s wrath by marrying. It worked. According to the 1851 census the now fifty-year-old Aaron, once more a Waterman, is living at 96 Green Row in Gosport, with his wife aged 49, who works as a laundress, and their son John aged 11. During this period Aaron’s father Robert dies in the workhouse, having spent 10 years of his life there[10].

Aaron alas couldn’t stay on the straight and narrow for long, he rocked the boat one last and final, bloody, time.

The Crimes Part 2

On Tuesday the 17th May 1853, Aaron did the unthinkable and stabbed his wife in the throat. Victorian society was shocked, apalled even, but as often happens in spousal abuse cases, the signs were there early on and, sadly, ignored.

One-week prior Aaron was sharpening his knife and, in an outburst overheard by a neighbour, said ‘I will do for her! I may as well be hanged first as last’[11]. Nor was this the only instance of menace as it was understood that ‘The prisoner had been frequently known to threaten to cut his wife’s throat, with whom he appeared to live on very indifferent terms’[12]. These were not idle words and he made good on this promise.

The newspapers disagree on the exact sequence of events, but it is likely that Aaron had been on a 2-day bender and on the morning in question had gone with his wife to the public house, where they had a pint of beer[13]. They walked back as normal, arrived home safely but then started to argue. Before his wife knew it, Aaron had leapt at her, knocked her down, and she fell between a mangle and washtub. Not content with winding her, Aaron knelt upon her person, unclasped his flick knife, and stabbed her in the throat twice. She fought back incurring multiple defensive wounds upon her hands[14].

Fortunately for Ann a passer-by, Ann Cassin (also spelled Cason), heard her shouts and ran over to discern the origin. Ann Cassin upon seeing this profane act, raised the ‘hue and cry’. James (or John) Elliot heard cries of ‘murder’ and ran to the location where he was presented by the spectre of Aaron Rungay stabbing his groaning wife[15]. Without thinking, he leapt at Aaron, pulled him off and placed the bleeding wife in a chair: meanwhile Aaron made his escape.

As Ann’s life ebbed, James ran for the surgeon, Dr. Riggall, and having secured the doctor’s services, fetched an Officer of the law: Constable Oliver.

Oliver arrived at the Rungay residence and saw the victim having her wounds dressed by the surgeon, her state was described as ‘nearly murdered’ and that had one been a ‘little deeper’ it would’ve cause ‘instant death’[16]. Oliver seeing that Ann was in good hands then sought out Aaron: had he fled the country? Was he even then in his boat on the high seas, free?

No. Aaron was found thirty minutes later in a pub on North

Street, smoking his pipe and drinking a pint of beer. A knife, still smeared in

blood, was found on his person. Upon being taken in custody, he was informed of

the charge of attempted murder. Hhis

response was ‘I hope I have – I hope that she is

dead’[17];

a man as callous as his seafaring hands. Ann’s wounds, meanwhile, had been

dressed and she was removed from her bloodied kitchen to her sister’s residence

at Ewer Common.

The trial should have been as open and shut as a concealed flick knife and, to an extent, it was. Mr. Pouldon conducted the case for the prosecution and Mr. Wise appeared for the prisoner: Aaron, it was asserted, was very deaf[18] at this point (although there is no mention of this in any other official record). Once the witnesses had testified, out came the medical examiner. It was noted that Mary had sustained two wounds to her neck, one an inch and a half long and an inch deep (almost killing her), the other two inches long and superficial, as well as a defensive wound to the ball of her thumb, an inch deep, and smaller cuts[19].

The evidence was utterly damning; indeed, he had condemned himself by his own words. What unassailable defence could Aaron produce in the circumstances? Little it would seem, telling the police ‘I did not intend to do it, it was done accidentally, she was drunk at the time and I was drunk also’[20].

The decision was given to the jury to decide, not if the act had been committed as this was evident, but whether or not there had been an intent to murder as this proof of intent could potentially lead to capital punishment, or a lesser charge of attempting grievous bodily harm. Curiously, they opted for the latter in spite of the evidence. Not that it helped Aaron, ‘The Judge said that he could not conceive there was a single person present in court, out of the jury-box, who did not believe that it was done with the intent to murder and sentenced the prisoner to be transported for life’[21].

Imprisonment

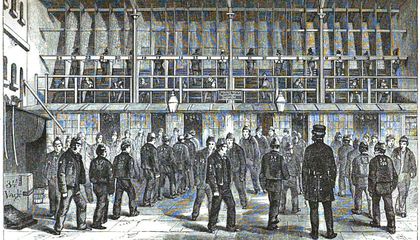

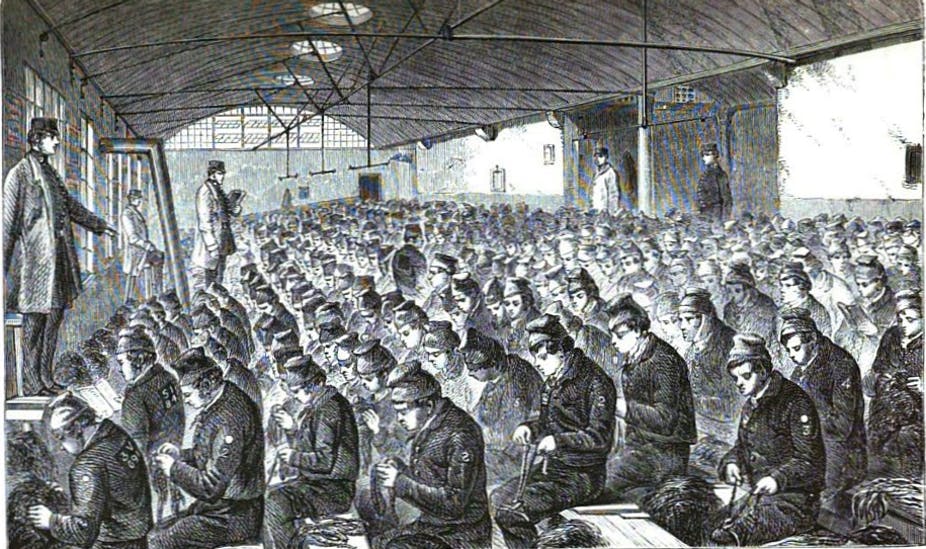

Aaron was held, likely in the county jail, for 5 months before being moved to Millbank on the 6th January 1854 and given the prison number 5386[22]: his feet at this time are noted as being deformed. He exhibited good behaviour, a trait seen throughout his penal servitude and was moved to a prison hospital hulk, the Stirling Castle, on the 7th of April that same year.

From the Stirling Castle to the Defence on the 30th September as prisoner 919 and, after only a brief spell at Boaz Island in Bermuda, was returned to the Defence[23]. During this period, aged 54, he (now prisoner 32) is described as being both invalided and infirm. From October 1856 until July 1857 he was on the Defence until the 17th July 1857 where he is moved to Millbank. Aaron was in Millbank for less than two months when he was moved to Lewes on the 1st September 1857[24]. Given a new prisoner number, 41, Aaron continued to display very good behaviour and we have no extant instances of bad behaviour or punishment.

Finally, on the 22nd March 1860, Aaron is moved to Woking Convict Invalid prison and given the prisoner number 213: this would be his last[25]. Whilst his behaviour remained very good during this period, at one point saving the life of a warder when a fellow inmate attacked him, his condition deteriorated; in the first years he was described as infirm, latterly as crippled, until in 1864 he was finally described as lame[26]. It is likely that by this time, Aaron was cell-bound and unable to move.

Aaron died on the 31st July 1864 and was buried likely in the pauper section of Brookwood cemetery[27].

Aftermath

Aaron’s legacy, if it may be called as such, was that of a

poor father passing bad habits to his son. John Rungay spent his year’s in and

out of the workhouse and prison, son of a disfigured mother and a disgraced

father, he died in an insane asylum in 1876 aged just 37.

[1] Salisbury and Winchester Journal, ‘Conviction’ (1853).

[2] (Chaplinbooks.co.uk, 2019) <http://www.chaplinbooks.co.uk/insidestory10.pdf> accessed 18 September 2019.

[3] Salisbury and Winchester Journal, ‘Conviction’ (1823).

[4] Hampshire Chronicle, ‘Convictions’ (1826).

[5] England & Wales, Crime, Prisons & Punishment Browse, 1770-1935, Prison Hulks and Quarterly Returns, 1832

[6] Ancestry.co.uk. (1834). Prison Register – The Leviathan Hulk. [online] Available at:

[Accessed 1 Oct. 2019].No Title

No Description

[7] Search.findmypast.co.uk. (1832). Alverstoke Burial Registers. [online] Available at:

[Accessed 1 Oct. 2019].Create an account today

Create an account for free with Findmypast to discover your family history and build a family tree. Search birth records, census data, death records and more.

[8] Search.findmypast.co.uk. (1841). Census. [online] Available at:

[Accessed 1 Oct. 2019].Join Ancestry®

Begin your discovery today by exploring the world’s largest online family history resource!

[9] Search.findmypast.co.uk. (1845). Marriage Certificate. [online] Available at:

[Accessed 1 Oct. 2019].Create an account today

Create an account for free with Findmypast to discover your family history and build a family tree. Search birth records, census data, death records and more.

[10] Search.findmypast.co.uk. (1844). Burial Registers. [online] Available at:

[Accessed 1 Oct. 2019].Create an account today

Create an account for free with Findmypast to discover your family history and build a family tree. Search birth records, census data, death records and more.

[11] Britishnewspaperarchive.co.uk. (1853). Hampshire Telegraph. [online] Available at:

[Accessed 1 Oct. 2019].Register | British Newspaper Archive

Register to get involved in the biggest newspaper digitisation project that’s ever taken place in the UK!

[12] Ibid.

[13] Ibid.

[14] Britishnewspaperarchive.co.uk. (1853). Portsmouth Times and Naval Gazette. [online] Available at:

[Accessed 1 Oct. 2019].Register | British Newspaper Archive

Register to get involved in the biggest newspaper digitisation project that’s ever taken place in the UK!

[15] Ibid.

[16] Britishnewspaperarchive.co.uk. (1853). Hampshire Telegraph. [online] Available at:

[Accessed 1 Oct. 2019].Register | British Newspaper Archive

Register to get involved in the biggest newspaper digitisation project that’s ever taken place in the UK!

[17] Britishnewspaperarchive.co.uk. (1853). Portsmouth Times and Naval Gazette. [online] Available at:

[Accessed 1 Oct. 2019].Register | British Newspaper Archive

Register to get involved in the biggest newspaper digitisation project that’s ever taken place in the UK!

[18] Britishnewspaperarchive.co.uk. (1853). Salisbury and Winchester Journal. [online] Available at:

[Accessed 1 Oct. 2019].Register | British Newspaper Archive

Register to get involved in the biggest newspaper digitisation project that’s ever taken place in the UK!

[19] Ibid.

[20] Britishnewspaperarchive.co.uk. (1853). Portsmouth Times and Naval Gazette. [online] Available at:

[Accessed 1 Oct. 2019].Register | British Newspaper Archive

Register to get involved in the biggest newspaper digitisation project that’s ever taken place in the UK!

[21] Britishnewspaperarchive.co.uk. (1853). Hampshire Telegraph. [online] Available at:

[Accessed 1 Oct. 2019].Results for ‘”aaron rungay”‘ | Between 1st Jan 1850 and 31st Dec 1899 | British Newspaper Archive

Your search results for “aaron rungay”: 10 newspaper articles contained information about “aaron rungay” filtered by: Date from: 1st Jan 1850 – Date to: 31st Dec 1899

[22] Ancestry.co.uk. Prison Register – Millbank. [online] Available at:

[Accessed 1 Oct. 2019].Create an account today

Create an account for free with Findmypast to discover your family history and build a family tree. Search birth records, census data, death records and more.

[23] Ancestry.co.uk. Prison Register – Stirling Castle Hulk. [online] Available at:

[Accessed 1 Oct. 2019].Create an account today

Create an account for free with Findmypast to discover your family history and build a family tree. Search birth records, census data, death records and more.

[24] Search.findmypast.co.uk. (1857). Quarterly Return – Lewes Prison. [online] Available at: https://search.findmypast.co.uk/record?id=TNA%2FCCC%2FHO8%2F133%2F143&parentid=TNA%2FCCC%2FHO8%2F0096424 [Accessed 1 Oct. 2019].

[25] Search.findmypast.co.uk. (1860). Quarterly Return – Woking Convict Invalid Prison. [online] Available at: https://search.findmypast.co.uk/record/browse?id=tna%2fccc%2fho8%2f144%2f265 [Accessed 1 Oct. 2019].

[26] Search.findmypast.co.uk. (1864). Quarterly Return – Woking Convict Invalid Prison. [online] Available at:

[Accessed 1 Oct. 2019].Create an account today

Create an account for free with Findmypast to discover your family history and build a family tree. Search birth records, census data, death records and more.

[27] Ibid.