Holloway Prison, known as the New City of London Prison upon first opening in 1852, became the largest female only prison in Europe by 1902[1]. Although initially a mixed sex prison, totaling 436 cells with only 60 filled by women, in 1903 it became a women’s prison with the capacity for 949 female inmates[2]. Construction for the prison began in 1849 under the designs of James Bunstone Bunning, costing an estimated £91,000 and spanning across 10 acres of land[3].

The prison had a long history and saw the detainment of many famous names. After over 160 years, the prison was closed in 2016 when the institution was sold to Peabody with the aim of constructing affordable housing in its place[4].

The Suffragette Movement

Holloway became a focal point of the suffragette struggle in the early twentieth century, with more than 300 suffragettes seeing the inside walls of the prison[5]. During this time, Holloway Prison made a name for itself for being the site of the Suffragette’s hunger strike and consequently the force feeding that the Suffragettes endured beginning with Marion Wallace Dunlop in 1909. This process involved the prison guards forcing tubes down the inmates’ throats to ensure that they did not die of malnourishment. The severity and national backlash of this movement led to the Cat and Mouse Act in 1913 which brought in legislation permitting women on hunger strike to be released back into the community, only for them to be re-arrested once deemed healthy enough[6].

The Suffragettes sought to expose the treatment they endured whilst incarcerated through sending letters to sources outside of the prison walls as well as speaking to the press, about their experiences in prison, upon release[7]. The hunger strike was one of the many attempts made by the suffragettes to prove themselves as political prisoners and fight against prison discipline which often followed a class structure, favouring those who came from wealth over the working-class women[8]. Incarceration was not enough to silence the Suffragettes, and their fight for freedom was somewhat amplified by their imprisonment at Holloway, uniting women of all social classes under a shared experience and encouraging further protests both within and outside of the prison[9].

Executions

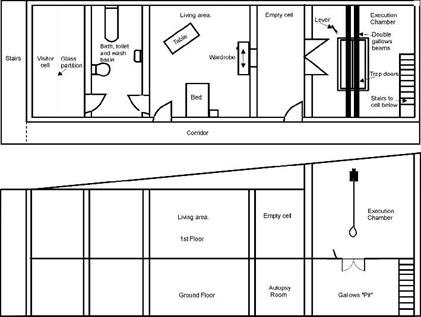

When turned into a female-only institution, Holloway Prison saw the addition of an execution facility, situated at the end of the B wing[10]. In total, between 1903 and 1955, five women’s lives were ended at Holloway through execution, which was a third of all the female hangings in twentieth century England[11]. The last of these women was Ruth Ellis, the final woman to be executed at Holloway and in Britain at large. Convicted of the murder of her boyfriend David Blakely, Ellis was executed on the 13th July 1955[12]. Once rebuilt in 1970, the buried remains of the five executed women were moved to a churchyard in Buckinghamshire under assumed names to prevent vandalism or illegal exhumations[13].

Inmates You Might Know

Oscar Wilde was sentenced to two years imprisonment and hard labour for his homosexuality in 1895 and served part of this sentence in Holloway Prison. It was during his incarceration that he received his inspiration for his final literary work The Ballad of Reading Gaol, before being released and dying in 1900 amidst seeking exile in France[14].

The Pankhurst women all saw the inside walls of Holloway Prison at one point in their lives. Christabel was convicted for interrupting a liberal party meeting to demand voting rights for women in 1905, Sylvia followed suit in 1906 when she was arrested for starting a protest in the House of Commons and finally, Emmeline was convicted in 1912 for conspiracy to commit property damage[15].

Mary Elizabeth Wilson, often referred to as the Merry Widow of Windy Nook, was sentenced to death in 1858 for the poisoning and consequent murder of two of her four husbands. However, due to her old age, this was changed to a life sentence and Wilson died during her incarceration in Holloway Prison[16].

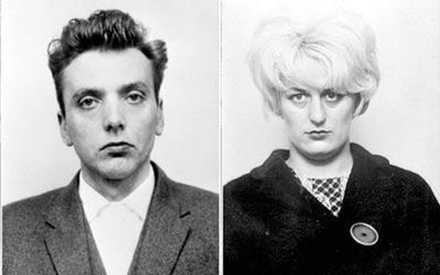

Myra Hindley, a serial killer who worked with counterpart Ian Brady, was convicted for the rape and murder of five small children in 1966 which later came to be known as the Moors Murders. Found guilty of the murder of two of the five children, Hindley was jailed for life and eventually died of respiratory failure in 2002, whilst incarcerated[17]. Hindley also gained a reputation whilst in Holloway Prison for her failed escape attempt, aided by her partner and prison guard Pat Cairns[18].

[1] Sullivan, Paul, ‘Goodbye Holloway’, Inside Time: The National Newspaper for Prisoners and Detainees, (31st Jan 2016)

[2] Sullivan, Paul, ‘Goodbye Holloway’, Inside Time: The National Newspaper for Prisoners and Detainees, (31st Jan 2016)

[3] Capital Punishment, ‘Holloway Prison’ [online], available at http://www.capitalpunishmentuk.org/holloway.html#:~:text=Executions%20took%20place%20at%209.00,Holloway%20between%201903%20and%201955. [accessed on 20th October 2020]

[4] ‘Holloway Prison: Up to 1,000 Homes to be Built in £82m deal’, BBC News, (2019)

[5] Historic England, ‘Holloway Prison and the Fight for Freedom’, [online] available at https://historicengland.org.uk/research/inclusive-heritage/womens-history/suffrage/hmp-holloway/, [accessed on 20th October 2020]

[6] Historic England, ‘Holloway Prison and the Fight for Freedom’, [online] available at https://historicengland.org.uk/research/inclusive-heritage/womens-history/suffrage/hmp-holloway/, [accessed on 20th October 2020]

[7] Davies, Caitlin, ‘From Prison To Parliament: The Suffragettes & Holloway’, Museum of London, (2018)

[8] Davies, Caitlin, ‘From Prison To Parliament: The Suffragettes & Holloway’, Museum of London, (2018)

[9] Purvis, June, ‘The Prison Experiences of the Suffragettes in Edwardian Britain’, Women’s History Review, 4:1, pp. 103-133

[10] Capital Punishment, ‘Holloway Prison’ [online], available at http://www.capitalpunishmentuk.org/holloway.html#:~:text=Executions%20took%20place%20at%209.00,Holloway%20between%201903%20and%201955. [accessed on 20th October 2020]

[11] Capital Punishment, ‘Holloway Prison’ [online], available at http://www.capitalpunishmentuk.org/holloway.html#:~:text=Executions%20took%20place%20at%209.00,Holloway%20between%201903%20and%201955. [accessed on 20th October 2020]

[12] Capital Punishment, ‘Holloway Prison’ [online], available at http://www.capitalpunishmentuk.org/holloway.html#:~:text=Executions%20took%20place%20at%209.00,Holloway%20between%201903%20and%201955. [accessed on 20th October 2020]

[13] Kennedy, M., 2015. Holloway prison closure will be mourned by few. The Guardian, [online] Available at: <https://www.theguardian.com/society/2015/nov/25/holloway-prison-closure-fearsome-reputation> [Accessed 10 November 2020].

[14] BBC Radio 4 Defoe, ‘Bang to Writes: The Literary Greats who Did Jail Time’, [online] available at https://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/articles/WPxZ5NXT6NYzYQH2KcpK6/bang-to-writes-the-literary-greats-who-did-jail-time, [accessed on 28th October 2020]

[15] Crime and Investigation, ‘Famous Inmates of Holloway Prison’, [online] available at https://www.crimeandinvestigation.co.uk/article/famous-inmates-of-holloway-prison, [accessed on 26th October 2020]

[16] Crime and Investigation, ‘Famous Inmates of Holloway Prison’, [online] available at https://www.crimeandinvestigation.co.uk/article/famous-inmates-of-holloway-prison, [accessed on 26th October 2020]

[17] Biography, ‘Myra Hindley’ [online] available at https://www.biography.com/crime-figure/myra-hindley, [accessed on 29th October 2020]

[18] Crime and Investigation, ‘Famous Inmates of Holloway Prison’, [online] available at https://www.crimeandinvestigation.co.uk/article/famous-inmates-of-holloway-prison, [accessed on 26th October 2020]

Written by Danielle Yates