Introduction

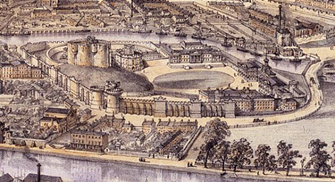

Throughout the centuries York Castle has been a Norman fortress, a Royal Palace, a court of justice, a Royal Mint, a prison and an administrative centre for the county. It was originally built in 1068 by William the Conqueror to consolidate his power in the North[1]. Today the site still hosts Clifford’s tower, a remnant of the original castle, and the York Castle Museum where visitors can learn about the transformation of the Castle. The most famous inmate associated with York Castle Prison is Dick Turpin, the romanticised Highway man of the 18th century, who spent his final night in the cells at the prison before his execution.

History and Transformation

The construction of the debtors prison began in 1701 and was completed in 1705, however the Castle did have a gaol for many years prior to that and is cited in several historical sources. Prisoners ranged from local characters to figures entwined within the history of The United Kingdom; hostages from Wales, prisoners of war brought from Ireland during the early campaigns of conquest and Scottish nobility have all been incarcerated in the Castle at the pleasure of English Kings[2]. There is also mention of a prison specifically for females built between 1237 and 1241, by local priest John Piper of Middleham[3]. Over the years the gaol and female prison were continually added to and expanded in line with demand, after a visit to the Castle in 1244 Henry III decided to rebuild the whole castle in stone[4]. Prior to the building of the debtors prison in 1701, described by Daniel Defoe as ‘the most stately and complete of any in the Kingdom’, the Castle as a detainment facility was far from adequate[5].

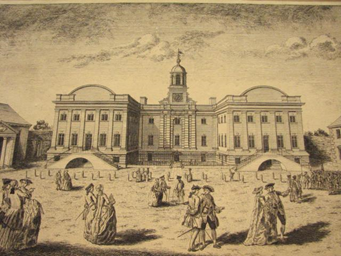

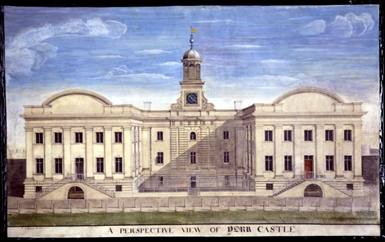

In 1636 the keeper petitioned the Privy Council of its ruinous condition and in 1653, warders complained that prisoners had broken through weak walls of the gaol and escaped[6]. The Debtors prison that followed was a grand building in the style of English Baroque, designed by Yorkshire man William Wakefield and built to reflect county pride[7]. In 1780 the female prison was also redesigned and rebuilt, in keeping with the architectural design; it was then enlarged in 1803. Due to the grand stature of the building, the prison soon became a tourist attraction, as this etching from the 18th century shows gentry ‘enjoying views of the prison and the prisoners’[8].

William Lindley, 1759

Despite the prison’s grand redesign in 1701, by the early 19th century it was in need of urgent improvements. After visiting several prisons in the North and Scotland, in 1818 philanthropist and writer JJ Gurney described York Castle prison as although having ‘some excellencies and great capacities, it’s evils are very conspicuous’. [9] The Gaol Act of 1823 also required alterations to the prison to align with a national effort to improve the treatment of prisoners, including provisions for Chaplain visits, salaries for Gaolers and banning the use of irons and manacles[10]. As a result, the prison was redesigned in a Tudor Gothic style with work being completed in 1835.

This redesign saw a round tower for the Governors of the prison, with four radiating prison blocks in a semicircle as well as a 35 foot high gatehouse; all protected by a high stone wall. [11] The prison was considered to be the strongest such building in England, as it was built entirely out of stone in order to be both fireproof and secure[12]. The redesign of the prison also concealed the backyard of the female prison from public

View; the space was then used as a space for hangings from 1868 onwards[13].

Throughout the centuries York Castle was home to a gaol and then a prison, revered as ‘the most stately in the Kingdom’ by Daniel Defoe and saw many changes in line with parliamentary acts and local demand. However in 1900 it ceased to be a civil prison and was handed over to the War Department, to be used as a military prison until 1929[14]. The former Victorian Prison buildings have since been demolished and now house the York Castle Museum, holding exhibitions on Victorian life, the 1960’s, life in the prison and more.

Notable Inmates

The prison housed inmates from all walks of life, with the most notable being Dick Turpin; the infamous Highway Man of the 18th century who has since been romanticised through Victorian literature. Originally from Essex, Turpin committed a series of crimes before fleeing to Yorkshire where he lived under the alias of ‘John Palmer’. Under a new name, Turpin continued his old ways. The law eventually caught up with Turpin, when he sent a letter from a gaol in Beverly to his brother in Essex and his old teacher recognising his handwriting at the post office, identified ‘John Palmer’ as the murderous Highwayman Dick Turpin.[15] Turpin was then moved to York Castle where he spent his final days, before he was executed by hanging in April 1739. Through historical debate, literature and pamphlets from the time, it has been argued that Turpin had an unfair trial which ultimately led to an easy prosecution. Turpin protested at his trial that he thought he would be tried in Essex and therefore had “not prepar’d for my defence”[16]. Turpin found fame after his death when his story was immortalised in Harrison Ainsworth’s bestseller ‘Rookwood’ in 1834; with a fictional Turpin riding from London to York on his horse Black Bess[17]. This romanticized Victorian image of Turpin has continued to attract and capture the interest of tourists, who can visit the cell where Turpin spent his final days at the York Castle Museum. Turpin’s grave can still be visited, housed in a small cemetery in the city.

Other famous inmates also include Elizabeth Boardingham, who was the last woman in Yorkshire to be burnt at the stake. In 1776 Boardingham and her lover Thomas Aikney killed her husband, John Boardingham, and the pair where both sentenced to death for the murder; Aikney by hanging and Boardingham executed by burning at the stake[18].

The colourful history of the various gaols and then the 18th century prison lives on through York Castle Museum; where visitors can look around some of the cells which have been preserved and experience what life was like for those unfortunate enough to be imprisoned there.

[1] Royal Commission on Historical Monuments, An Inventory of the Historical Monuments in City of York, Volume 2, the Defences, Her Majesty’s Stationary Office, 1972, pages 57-86

[2] T.P. Cooper, The history of the Castle of York from its foundation to the present day, with an account of the building of Clifford’s Tower, London E Stock, 1911, page 90

[3] H C. Maxwell Lyte, Calendar of Close Rolls, Henry III: Volume 4, 1237-1242, His Majesty’s Stationary Office, 1911

[4] RCHM, An Inventory Volume 2, pages 57-86

[5] D. Defoe, A Tour Thro’ the Whole Island of Great Britain, Volume III, 1748, page 167

[6] Calendar of State Papers Domestic: Charles I, 1636-7, ed. John Bruce, Her Majesty’s Stationary Office, London, 1867

[7] The Debtors Prison, History of York, http://www.historyofyork.org.uk/themes/tudor-stuart/the-debtors-prison(Accessed 13th July 2020)

[8] W Lindley, 1759, York Art Gallery

[9] J.J. Gurney, Notes on a visit made to some of the prisons in Scotland and the north of England, in company with Elizabeth Fry : with some general observations on the subject of prison discipline, London, 1819, page 234

[10] Living Heritage, Police, Prisons and Penal Reform, www.Parliament.uk, https://www.parliament.uk/about/living-heritage/transformingsociety/laworder/policeprisons/overview/centralcontrol/ (Accessed 13th July 2020)

[11] A.W Twyford, Records of York Castle – Fortress, Courthouse and Prison, Alcester: Read Books, 2010

[12] R. Sears, A New and Popular Pictorial Description of England, Scotland, Ireland, Wales and the British Islands, Robert Sears: New York, 1847

[13] L. Butler, Clifford’s Tower and the Castles of Yorkl, London: English Heritage, 1997

[14] Cooper, The History of the Castle, 312

[15] J Sharpe, The Myth of the English Highwayman, London: Profile Books, 2005

[16] The whole Trial of the notorious Highwayman Richard Turpin, at York Assizes, on the 22d Day of March, 1739, before the Hon. Sir William Chapple, Kt, Judge of Assize, and one of his Majesty’s Justices of the Court of King’s Bench. Taken down in Court by Mr. Thomas Kyll, Professor of Short Hand. To which is prefix’d, an exact Account of the said Turpin, from his first coming into Yorkshire, to the time of his being committed to York castle communicated by Mr Appleton of Beverly, Clerk of the Peace for the East – Riding of the said County. With a Copy of a letter which Turpin received from his father, while under Sentence of death, &c (Ward and Chandler, York, 1739) 19.

[17] W Ainsworth, Rookwood: A Romance, London: Richard Bently, 1834

[18] Elizabeth Boardingham, History of York, http://www.historyofyork.org.uk/themes/georgian/elizabeth-boardingham (Accessed July 7th 2020)

Written By Lydia Caldwell-Ball